Understanding the Misunderstood: An Introduction to the Rasalila

The concept of Krishna’s Rasalila is often misinterpreted and, at times, even distorted. Many have attempted to explain this complex and intricate narrative, but few have succeeded in presenting it clearly and accessibly to the average person. While recent discussions, such as those in the Jaipur Dialogs podcast featuring Ami Ganatra ji and Sanjay Dixit ji, have aimed to dispel popular misconceptions, there is a need for a deeper, more comprehensive exploration to bring true clarity. Therefore, we will attempt to elucidate the Rasalila to the best of our ability, with the blessings of Lord Krishna.

The Power of the Lila: Approaching the Rasalila

Today, we embark on an exploration of the supremely significant episode of the Rasalila. The very act of listening to the story of the Rasalila possesses the power to purify the listener, to burn away all accumulated sins. If one approaches the narrative with a pure mind, understanding it as the divine play (lila) of the Supreme Being, immense rewards are yielded. By striving to comprehend the hidden secrets within this story, one is granted the opportunity to see it as the truly divine and celestial play that it is. In my understanding, there is perhaps no greater lila in all of creation than the Rasalila.

The Common Misconception: Beyond Sensual Pleasure

Unfortunately, many individuals, upon hearing the term “Rasalila,” conjure images of Krishna engaging in sensual pleasures with numerous women. This is a profound misunderstanding of its core purpose. The profound meaning of the Rasalila is challenging to convey through any other means, and thus, it is presented in this specific narrative format. I will endeavor to explain the multiple layers of its meaning as we proceed, and I implore you to attempt to grasp the broader perspective from which it should be understood.

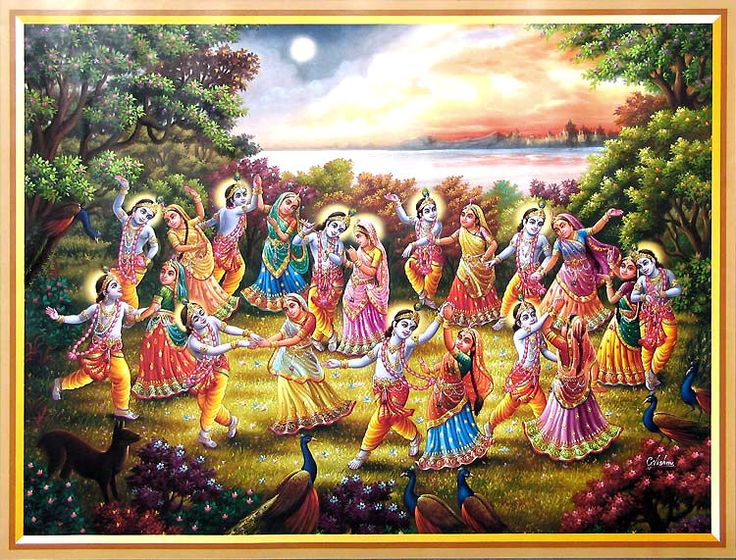

The Setting: A Night of Divine Melody

The season of autumn (Sharad) arrived, bringing with it a full moon night, illuminated by beautiful moonlight. This time of year coincides with the celebration of Sharad Navaratri. The moon of the Sharad season has a special designation; it is called the “Parinita Chandra,” meaning the “mature moon.” The moonlight experienced during this period is exceptionally beautiful. On such an autumn full moon night, Lord Krishna stood on the sandy banks of the Yamuna River. Standing there, he commenced to play a captivating and enchanting melody upon his flute.

The Call of the Flute: The Gopikas’ Response

It is crucial to approach this part of the story with utmost care and attention. There were numerous cowherds (Gopas) and cowherd women (Gopikas) present. However, the narrative emphasizes only the women, not the men. At that very moment, some of the Gopikas were occupied with various tasks: they were letting the calves out to milk the cows, some were in the midst of the milking process itself, while others were in the process of placing the fresh milk onto the stove, and yet others were removing the boiled milk from the fire. This was not a single, cohesive scene; rather, it encompassed different homes, and different times. This is not unusual; for example, while milk might be boiling in one house in the morning, their neighbors could be in the process of taking it off the stove in. Elsewhere, someone was preparing to churn butter, and in another household, a mother was on the cusp of breastfeeding her infant.

It was precisely then that they heard the sound of Krishna’s flute, the Vamsiravam. The instant they heard it, some of the Gopikas envisioned Lord Krishna in their minds. They conjured an image of the Supreme Krishna playing that mesmerizing melody, embraced him tightly in their imaginations, and, overwhelmed with ecstasy, departed from their physical bodies at that very moment.

The Conflict: Social Expectations and Divine Yearning

Yet, others defied the attempts of their husbands, fathers-in-law, brothers-in-law, and sons to impede them. Declaring, “We must participate in the Rasalila with Krishna; we must experience bliss through him,” they ran towards the location where Krishna was playing his flute.

Upon seeing them all, Krishna said, “You are all married women. You have husbands, children, in-laws, and parents. If women run to another man at such an inopportune hour, wouldn’t it destroy their honor and reputation? If your father-in-law were to discover this, wouldn’t it ruin your family life? Wouldn’t it lead to the dissolution of your marriages? If your husbands learned of this, wouldn’t the situation become dangerous? Wouldn’t it bring shame upon your parents? Wouldn’t your sisters-in-law mock you, and your sons feel humiliated? Why have you come here in the middle of the night?”

With tears streaming down their faces, they replied, “Krishna, you know why we have come. After coming all this way to find happiness through you, do you now ask us why we are here?”

Parikshit’s Doubt: Questioning the Lila

At this juncture in the narrative, even King Parikshit, who was listening to the story, was astonished. He stood up and exclaimed, “Stop, stop, stop! This is very strange. Everything you have told me so far has been fine, but what is this? Night falls, he plays the flute, and all these women run to him, pushing aside their men who try to stop them? How can they ask him for pleasure? Is it proper for the Lord to do such things? He who is meant to establish and protect Dharma (righteousness), should he incite such feelings of desire in the wives of others?”

Guru Shuka’s Explanation: Understanding Divine Action

Shukabrahma, the narrator, responded, “Do not be hasty, Parikshit. Try to listen to the Rasalila carefully. You will understand.”

The Significance of the Setting: Time and Divine Will

Now, one could choose not to elaborate further on the lila story here and simply conclude the story by stating, “This is the lila of the Lord. Mortals do not have the authority to question the rightness or wrongness of God’s actions.” Or for example, if a husband and wife are arguing, an outsider cannot intervene and dictate how the husband should or shouldn’t argue; that is the very nature of their relationship. Similarly, he is the Lord of the universe. Humanity possesses no right to question or criticize anything he chooses to do in this world. That could be said, ending the lila, and few would object, because Shuka himself said this. However, the narrative will endeavor to present it from another angle—a humble attempt to shed more light on its significance.

Consider this: Lord Krishna is standing on the banks of the Yamuna River on an autumn full moon night, playing his flute. Give careful consideration to this situation.

The location for the divine flute playing—the bank of the Yamuna—is not incidental but deeply symbolic. To understand its significance, one must recall the river’s origin. The Yamuna is the daughter of the Sun God, and her brother is Yama, the god of death. This lineage establishes the river as a powerful symbol for the ceaseless flow of time itself.

As time relentlessly flows onward, like the river’s current, all beings that come into existence in this world are inevitably carried toward their end. The scale of this cosmic cycle of birth and death is immeasurable. Were one asked to state the precise number of creatures, human or otherwise, that died or were born at a specific instant like 12:10:01, no one could possibly answer. Such knowledge is beyond mortal capacity.

Only the Lord knows, for he is not bound by time but is the very embodiment of time itself. He is the ultimate force who both creates life and, through his agent Yama, brings about its end. By playing his flute on the bank of the Yamuna, he presides over the very current of existence, demonstrating his mastery over life, death, and time.

The Divine Grace: The Role of Autumn and the Pure Mind

Therefore, the Yamuna symbolizes the flow of time. He selected the riverbank as his stage, signifying: “In this stream of time, you have journeyed through countless births, inhabiting countless bodies. Now, through my causeless mercy, I have chosen to uplift certain souls.” This is known as Ishwara Sankalpa (divine will). Why does God resolve to do this? The scriptures describe it as “nirhetuka kripa” – causeless grace in his cosmic dream. There is no further explanation for it.

The underlying cause of this event is the Lord’s grace, which manifested as the spontaneous thought to play the flute. The timing chosen for this divine act—the Sharad season, during Sharad Navaratri—is profoundly symbolic. The reason for selecting autumn is that its sky is characteristically clear of clouds, pure, and filled with luminous white moonlight.

This pristine external environment serves as a direct metaphor for the internal state required to perceive the divine. The music of the flute can only be heard by those whose minds mirror the clarity of the autumn sky. In such minds, the turbulent qualities of Rajas (passion) and the obscuring nature of Tamas (ignorance) have greatly diminished. What shines forth instead is the pure light of Sattva (goodness). Therefore, only those souls who constantly contemplate Krishna, and have thus achieved this state of inner purity, are capable of perceiving his celestial music and are irresistibly drawn to its call.

The Nature of the Sound: Beyond Physical Sensation

First, conventional sound is non-selective. In a public lecture, for instance, everyone in the hall hears the speaker; sound does not choose its recipients. Likewise, a stimulus meant to excite would typically affect both men and women. Krishna’s flute music, however, was heard in a captivating manner only by the Gopikas, indicating it was not a mere physical vibration but a targeted spiritual call.

Second, attributing the Gopikas’ reaction to carnal desire is logically inconsistent. Lust is a persistent internal state that does not require a specific trigger; an individual consumed by it would have acted at any time. The scriptures affirm this with the axiom, “Kamaturanam na bhayam na lajja” (For the lustful, there is neither fear nor shame), suggesting a constant disposition. The Gopikas, however, were mobilized into a state of frenzy only upon hearing the flute.

Furthermore, their behavior contradicts the typical conduct associated with illicit desire. A woman pursuing an affair would act with secrecy and discretion. The Gopikas acted with flagrant openness, publicly pushing aside husbands, brothers-in-law, and fathers-in-law to run towards the music’s source. This open defiance is implausible if motivated by simple lust.

Finally, the scale of the event challenges any mundane explanation. While the behavior of a single woman might be dismissed as promiscuity, the fact that thousands of Gopikas acted in perfect unison points to a powerful, collective, and transcendent experience. The logical question then arises: when the Gopas tried to stop them, were their efforts simply brushed aside? It is improbable that the men would stand by as helpless bystanders. The inability of the Gopas to restrain them suggests the Gopikas were compelled by an irresistible force, one that superseded all worldly attachments and social authority.

The Core Meaning: Atma Vardhanam and the Soul’s Journey

Why did this occur within the Rasalila? We will provide a singular answer that can be applied to all these questions.

Do you know what happened to the Gopikas when they heard the flute? The text describes it as “ananga vardhanam.” With this phrase, the sage Vyasa cast a spell of enchantment upon us all. “Ananga” means “the bodiless one”—like the Manmadha, the god of love. Consequently, “ananga vardhanam” on the surface level translates to the arousal of lust. If one interprets it through the lens of the Rasalila’s title, that is the meaning that one derives.

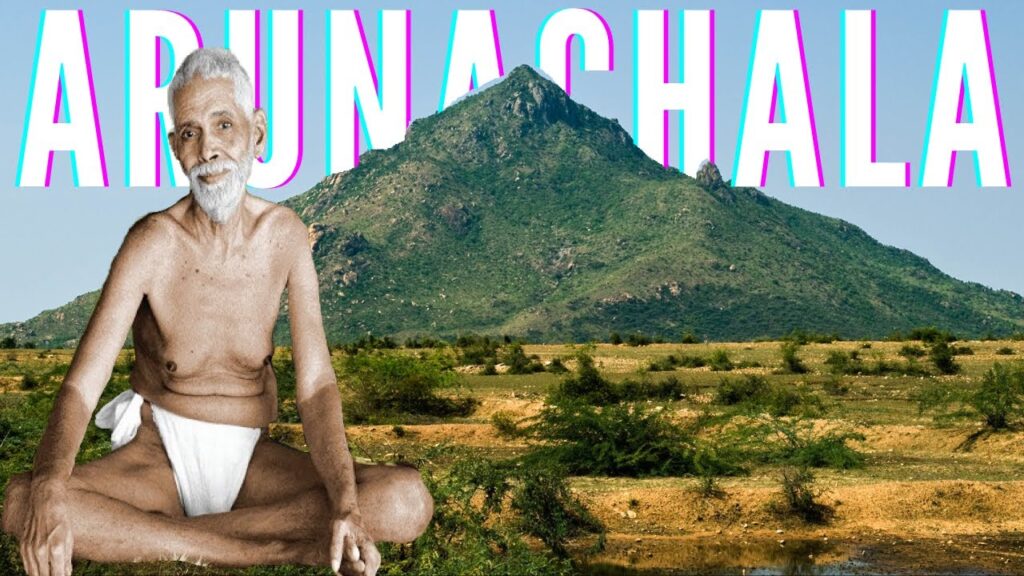

However, “ananga” also means “that which is not the body.” What is not the body? The Atma (the soul). Thus, “Atma vardhanam” signifies they became oriented towards the soul. The call of the Lord reached those who were worthy. Lets take an example. A long time ago, before Bhagavan Ramana Maharshi had undertaken his austerities or realized the Self, he was merely a young boy walking down the street. A relative of his was returning from a pilgrimage to Arunachala. The boy posed a simple question: “Where are you coming from?” The man responded, “I am coming from Arunachala.” That is it. That was the sound of the flute.

The Example of Ramana Maharshi: The Awakening Within

The young boy, whose name was Venkataraman, stopped and inquired, “What did you say?”

“I am coming from Arunachala.”

In that instant, he experienced a connection that spanned countless lifetimes. He felt his hair stand on end, and an inexplicable joy welled up within him. “Arunachala? Where is that?” he asked. The man replied, “You don’t know Arunachala? It’s Tiruvannamalai.” That was the spark ignited with the wound of the words Arunachala…Tiruvannamalai.

After that profound spark, one day he was sitting in an upstairs room and had a death-like experience. “This body is falling away,” he thought. “I know that this body is falling away. Because I am the one who knows it, ‘I’ am not this body. The one within is ‘I’. This ‘I’ is watching this body fall. After it falls, they will take it to the cremation ground and burn it. What will happen to the ‘I’ that is watching? Therefore, this body is not ‘I’.” That feeling of ‘I’ awakened within him. That was Vairagya (dispassion). After that, he never looked back. From then on, he was always absent-minded. His family would ask, “Why are you so distracted? Why aren’t you studying?” Soon after, he left for Arunachala and never returned in his lifetime. His soul merged with Arunachala.

The Call and the Chosen: The Grace of God

Now, what would you call this? Did not everyone hear the words, “I am coming from Arunachala”? Why did it transform only Venkataraman into Bhagavan Ramana, a world teacher? Because the grace of God had descended upon him. This is what it means to hear the flute’s call in gopikas case.

The Role of the Gopikas: A Symbol of the Soul’s Yearning

So, what transpired when they heard (flute) it? It was “ananga vardhanam”—they became oriented towards the Self. Why is this narrated through the Gopikas, and not the men? In this world, we speak of husband and wife, but in the scriptures, there is only one relationship. All are female, and all must attain the one true husband, the Lord of the Universe. He is the Pati (Lord/Husband) of the cosmos, the eternal, auspicious, and unchanging one. He is Vishveshwara or Narayana, whatever name one chooses to call him. Since all souls seek to attain him, we are all depicted as female, and hence in lila symbolically its gopikas.

Beyond Gender: The Symbolism of Deities

Most Hindu deities are represented with specific attributes that convey their divinity, virtues, and roles within puranas. That is why you will notice that all deities are depicted in a particular way, for example Veera Venkata Satyanarayana Swamy, who has a grand mustache, signifying his masculine form. He is the ultimate Purusha (masculine principle). The presence of a mustache on Veera Venkata Satyanarayana Swamy communicates attributes like valor, authority, and power, reinforcing his status as a protector and an embodiment of masculine energy.

We, in our embodied forms, are the changing element, and we must realize the unchanging truth, which is God. This realization dawns within certain souls. Those who received this inner call were the ones who heard the flute of Lord Krishna. Therefore, it was “ananga vardhanam” for them. The story sounds like an arousal of lust, but is it about kama (lust) or moksha (liberation)? It is about moksha definitely.

The Path of Devotion: Madhura Bhakti and the Union of Souls

So, who are all these Gopikas? They are seekers of the bliss of the Self (Atmananda). This bliss cannot be described in words. How, then, can it be conveyed? Through Madhura Bhakti—the path of sweet, intimate devotion. So, this is expressed through the analogy of a lover and the beloved.

The Language of Mystics: The Lover and the Beloved

It’s a fascinating thing: Great sages, the liberated souls who are qualified for moksha and are just living out their remaining prarabdha karma in a physical body, they all compose hymns of a similar nature. In their and works and sayings, they cast themselves as the heroine (nayika) and the Supreme Lord as the hero (nayaka), pleading, “Unite with me somehow.” For example Ramana Maharshi wrote a hymn to Arunachaleswara called “Arunachala Akshara Manamala,” where he says, “I am a woman, you are a man, we must be married. How can you not accept me?” Did Ramana Maharshi not know that he was a man and Arunachaleswara was a form of God? It’s not about that. The behavior of a jnani (a realized one) is very peculiar. When once Seshadri Swami asked Ramana Maharshi, “They say that worshiping Arunachaleswara quickly bestows his grace. What do you say?” he didn’t answer. After being asked about 10-15 times, Ramana finally said, “Who worships whom?” There is only one entity. This is the kaivalya and moksha state a jnani reaches.

The Experience of Samadhi: The Unitive State

The bliss of the Self realization, experienced in the state of Samadhi, where one abides as the inner Self, is so immense that the physical body can barely contain it. It cannot be expressed in words. So how can this bliss experience be described? It can be described effectively only through the union of a lover and beloved. The union of the individual soul (Jiva) with the universal consciousness (Brahman) can be conveyed in no other experiential way. This is why the divine wedding (Srinivasa Kalyanam) is a central ritual. When we say we had a Kalyanam performed for Lord Venkateswara in Tirumala, it’s not that we, as mere mortals, are arranging God’s wedding. We are not Shukabrahma. We are not performing the wedding; we are attaining it. The union of Padmavati and Srinivasa represents the Jiva-Brahma Aikya (Amalgamation) Siddhi—the attainment of the union of the Individual and the Supreme. That is the spiritual significance of the Kalyanam.

The Structure of the Narrative: Madhura Bhakti as the Framework

Therefore, the Rasalila must be described as the coming together of lovers (Individual and the Supreme) (Gopikas which mean all of us and the Supreme Krishna); there is no other way convey this better in the scriptures. Hence, it is narrated through the lens of this Madhura Bhakti.

Krishna’s Words: The Test of Devotion

So, all these women went there, saw Krishna, and he told them to go home. Now, see how interesting this is. Lust is a fundamental anchor for the entire world. No one needs to be taught to engage in it. There isn’t an innocent soul in the world who needs someone to whisper in their ear, “My dear boy, you’ve come of age; you must now start love making and enter family life.” He will give the signals himself: “Will you arrange my marriage or not?” He will settle into worldly life.

The Contrast of Desires: Worldly versus Divine

A great soul, however, is different, as their desires are of a higher order. The life of Ramakrishna Paramahamsa provides a profound illustration of this principle. When Sharada Devi came to live with him as his wife, their initial meeting redefined the purpose of their union. He met her and posed a critical choice.

He acknowledged their marital bond but placed it within the vast context of reincarnation, noting the countless husbands and wives they both have had over millions of births. He then asked her directly: “In this life, as my wife, will you help me attain liberation, and as your husband, shall I help you, so we both achieve moksha? Or, because this knot has been tied, should we plunge into the mire of worldly existence? Tell me.”

Sharada Devi’s reply was unequivocal: “Let us help each other attain liberation. I will never pull you into worldly (Samsara) life.”

Thus, their marriage was transformed from a conventional social contract into a partnership for spiritual advancement. It served a higher purpose. For him, she was a manifestation of the Divine Mother Kali; for her, he was her spiritual master. Through this sacred re-conception of their relationship, both attained liberation.

The Perspective of the Great Souls: Renunciation of Worldly Attachment

So, did worldly desire function in Ramakrishna? No.

Similarly when Krishna said, “Go home to your husbands and children,” the words felt repugnant to them to gopikas. “We cannot listen to this,” they said. On the surface, the story makes it seem like they left their husbands out of lust. But it actually depicts the state of great souls. When Ramana Maharshi was meditating, people threw stones at him. Finally, a farmer took pity on him and led him to a mango grove. He made a small platform of sticks on a mango tree where Ramana could sit and meditate. Eventually, a relative recognized him, and his mother came to beg him to return home. Do you know what he wrote in the letter he left behind? The words that come from a self-realized person are amazing. “This one is going in search of its true source. No one need search for this. The fee for this was not paid with the money taken from the box.” He doesn’t say “I” or “for me,” showing he had no attachment to his body or identity. He signed it with no name, as he was no longer connected to name and form, but to the all-pervading Self. When his mother came and asked him to come home, he replied, “Who is the mother? Who is the son? Where is there to come from?” And he never left the caves of Arunachala.

The Misinterpretation and the Danger: Approaching the Rasalila with Understanding

So, for such souls, the call to “come home” sounds strange. What is home? Who is a wife? Who are the children? These relationships have existed for countless births. What are these attachments? They conclude that this birth is for attaining the Lord, not for worldly life.

Thus, while on the surface the story of the Rasalila sounds like the tale of promiscuous women acting out of uncontrollable lust, if you interpret it that way, you commit a terrible offense against God, his devotees, and liberated souls. Therefore, one should speak of the Rasalila only if one understands it; otherwise, it is better to remain silent.

The Gopikas’ Prayer: Seeking Liberation

What did the Gopikas say? They came to Lord Krishna’s feet, held them, and prayed, “O Lord! For those who serve your feet, the fear of worldly existence is dispelled. Please place your lotus hand, which bestows the great fortune of liberation, upon our heads and protect us.” Look at these profound words. Can you show me anywhere in this verse that they were driven by lust? “For those who serve your feet, the fear of worldly existence is dispelled.” Did they leave their worldly lives for lust or for liberation? They are asking for moksha.

Krishna’s Response: A Test of Devotion

But Krishna replied, “You should not have come, and you should not ask this of me. You run here in the middle of the night just because I played my flute and now you want to stay with me for pleasure? This is wrong. You must all go home.”

The Gopikas’ Perseverance: The Pursuit of Union

They cried, “Oh, after countless lifetimes of penance, our austerities have finally borne fruit, and we have reached you. And now you ask us to go back? We will not go back to our husbands. Do not say such a thing. They are worldly husbands, the cause of worldly bondage. We do not want that anymore. We want to merge with you, the Lord of the Universe.” They asked, “Does a bee, accustomed to the fragrance of the lotus, ever deign to go to any other flower?” A ‘pati’ (husband) is one who protects and sustains. You are the one with those qualities. You must give us refuge. We have been wandering for so many births. You must grant us liberation. We did not come here only to be sent back. Grant us that state of moksha from which there is no return.

The Supreme Lord was pleased with their words.

Standing Firm: The Path of the Jnani

It is one thing to go; it is another thing to stand firm. There is a huge difference. For example Ramana Maharshi went to Arunachala and stood firm. It was incredibly difficult. He tore off his sacred thread. He even cast away his loincloth, thinking, “When I am not this body, what is the need for all this?” He sat in meditation. They threw stones at him. He had his head shaved. He went into the Patala Lingam cave. Most people want to be where other people are; a jnani wants to be where no one is. He sat in the cave, and scorpions and insects bit him. His flesh rotted away, and blood crusted over, but he remained seated. It was Seshadri Swami who saw him and brought him out.

The Ultimate Experience: Brahmananda and Union

Such is their state—they abide in the bliss of Brahman. If one can withstand this, if one has the fortune of such strong dispassion, if one can stand firm in penance, seeking only God, then the Lord will manifest right there. The bliss experienced then is symbolized—it is depicted as a lover and beloved playing together. The individual soul (Jiva) unites with Brahman. The ecstatic experience of this Jiva-Brahma union is shown as the bliss of the union of lovers.

The Dance of the Divine: Symbolism in Action

So, in the Rasalila, on the surface, it appears as if many Gopikas are playing with Krishna. But is that the reality? No, it is a symbol. They are experiencing the bliss of Brahman (Brahmananda).

The poem describes them dancing with Krishna, their waists swaying, smiles on their faces, garlands intertwining, waistbands loosening, sweat pearling on their bodies, and their hair and earrings moving. They sang and danced with Krishna like flashes of lightning against a dark cloud. How can one Krishna engage with thousands of Gopikas at the same time? It represents how so many devotees can attain the union with Brahman simultaneously. “Between every two women, there was a Madhava (Krishna), and between every two Madhavas, there was a woman.” In the circle, Krishna, the son of Devaki, played his flute, with a Gopika, a Krishna, a Gopika, and so on. Any number of souls can experience the bliss of moksha at the same time.

The Inner Symphony: Yoga and the Path Within

While they danced, some played the veena, and others the mridangam. This is all symbolic of the inner experiences of a yogi. Before attaining self-realization through Ashtanga Yoga, the practitioner experiences intense perspiration, hears the sounds of flutes and veenas from within, and these are all signs of progress. Vyasa Bhagavan, unable to describe the ineffable bliss of the Self in words, has masterfully depicted it as this grand Rasalila.

The Celestial Witness: The Devas and the Rejoicing Within

The Devas (gods) are said to have watched this from the heavens. When beings engage in worldly pleasures, no one applauds; it is animalistic behavior. But when a soul, after countless births, is finally uniting with the Lord, the gods rejoice. Who are these gods? They reside within this very body. Each organ is presided over by a deity. That is why one of the primary causes of poverty is said to be washing one’s feet by rubbing one foot against the other. The Devas reside even in the feet. That is why we bow to the feet. A person’s spiritual power is concentrated in the nerves of the feet. Bowing the head is an act of humility, and in that humility, Lakshmi (goddess of fortune) resides.

So, when the scripture says the Devas watched from their celestial vehicles, it means the deities residing in the body rejoiced, thinking, “Finally, this body has served its purpose! With this body, he has realized and attained Brahman.”

The Dissolution of Self: The Return to the Source

The experience of Samadhi is one where all mental fluctuations and latent tendencies (vasanas) cease. The sense organs stop functioning, and one abides as the inner light of the Self. The bliss experienced in this state is so immense that it alone sustains the body, without the need for food or water. This state of being immersed in bliss is what is being described. This is the Rasalila experienced by the Gopikas with Krishna.

The Fall from Grace: The Return of the “I”

Then, a gentle breeze from the Yamuna, carrying the coolness of the water, blew to soothe the fatigue from their ecstatic dance. As they became slightly aware of the external world, a subtle thought arose within them: “I have attained the vision of the Self.” The moment the “I” returns, even to claim realization, one has slipped off from the peak. The moment they thought, “We are experiencing bliss with Krishna,” Krishna disappeared. This means they could no longer remain steady in the state of Samadhi.

The Yearning for Union: The Madman’s Quest

Now, their (Gopikas) agony is like that of a madman. A jnani is often called “unmatta” (madman) because his behavior seems crazy to the world. He wanders aimlessly, muttering to himself, sitting in solitude. He is connected to the ultimate reality, not the external world. Look at the state of the Gopikas now. They need Krishna. But who do they ask? They don’t ask people, “Have you seen Krishna?” They ask the trees and flowers: “O Punnaga tree, have you seen the one adored by all? O Tilaka tree, have you seen the one with a beautiful forehead? O Champaka tree, do you know where he is?”

The Peacock Feather: Celibacy and Divine Mystery

Potana’s famous poem in Telugu describes this beautifully: “O jasmine creepers, have you seen him? The dark-skinned one, the one with a beautiful smile, the one with lotus-like eyes, the one who showers grace, the one with a peacock feather in his hair… has he stolen our hearts and hidden among your bowers? Please tell us, is he not here?”

Potana deliberately used the words “the one with a peacock feather in his hair.” He did this because he knew that in the future, people might misunderstand the Rasalila and think Krishna engaged in physical relations with so many women. Why a peacock feather? Of all the creatures in the world, the peacock is the only one that conceives without physical union. During the rainy season, when dark clouds gather, the male peacock dances with its feathers spread. Overcome with joy at the sight of the first raindrops, a tear falls from its eye. The peahen drinks this tear and conceives. There is no physical contact. This is the secret of the Rasalila. The peacock feather symbolizes Krishna’s “askhalita brahmacharya” (unbroken celibacy), even while being surrounded by many women. He is the Supreme Brahman granting the union of Jiva and Brahman.

The Final Union: Returning to the Absolute

Eventually, they once again attained the grace of Lord Krishna and played in the waters with him, all experiencing union with the Absolute. This divine event is known as the Rasalila. It is hoped that this explanation has been able to reveal at least a little of its profound sanctity.

The Analogy of Fire: Parikshit’s Final Lesson

It is a secret to be understood through meditation. However, the sages understood the common listener’s mind. King Parikshit repeatedly asks, “But how could Krishna dance with the wives of others?” Finally, Vyasa gives him one last analogy. “If you cannot grasp the esoteric knowledge within this lila, then remember this one thing. Fire can burn a corpse. Does the fire that burned a corpse become impure and need to take a bath? No. The fire that cooked your food, did it gain merit? No. The fire in the yajna (sacrificial ritual) to which you offered oblations, did it gain any special status? No. Fire remains fire, regardless of what it touches. It is untainted by the objects it comes into contact with. If you can see Krishna in the same way, why should the Rasalila trouble anyone? Think of Krishna as that fire. He uplifted souls in the way he deemed fit. Why should it cause anyone distress? He has no attachment, which is why he wears the peacock feather. You can see that fire remains pure; why can you not see Krishna in the same way? If you cannot, it is a flaw in your vision, not in Krishna. If you listen to it this way, the Rasalila will liberate you.” Such is the supreme sacredness of the Rasalila.