The Life-Breath of the Bhāgavatam: Unveiling the Tenth Canto

The Tenth Canto (Daśama Skandha) of the Śrīmad Bhāgavatam is often regarded as its very life-breath—the radiant heart through which the entire scripture comes alive. It embodies the most mature, refined, and spiritually profound expression of divine truth within the Bhāgavatam’s twelve cantos. The earlier chapters prepare, purify, and elevate the seeker’s understanding; but in the Tenth Canto, all philosophical inquiry finds its culmination in the revelation of Bhagavān Śrī Kṛṣṇa’s divine play—His lila—as the highest embodiment of love, beauty, and truth.

It is said that one must read, hear, and contemplate the Daśama Skandha at least once in a lifetime, for it provides the mind with an eternal ālambana—a sacred point of anchorage. The mind, by its very nature, cannot remain still or unengaged. If not anchored to something sublime, it inevitably clings to the transient—restlessly chasing worldly pleasures, possessions, and fleeting sensations in its attempt to gratify the body and the senses.

And when the mind is left without a higher purpose, it becomes enslaved to lower impulses, revolving endlessly around material concerns. Yet, when it is consciously offered a noble and divine object of contemplation—such as the divine sports (Lila) of Śrī Kṛṣṇa—it finds peace and fulfillment. Anchored in the sacred narratives of the Tenth Canto, the mind ceases its wandering, for it has found its true home in the remembrance and contemplation of the Lord.

Thus, to engage the mind with the Daśama Skandha is not merely an act of devotion but a profound act of psychological purification. By giving the mind a pure and luminous object, we save it from the chaos of distraction and the decay of worldliness. The Bhāgavatam teaches that the mind, when absorbed in divinity, becomes not an obstacle but the very instrument of liberation.

All Paths Lead to Hari

In this profound section, Pothana unveils a spiritual secret through his poetic rendering of the Bhāgavatam. When Nārada addresses Dharmarāja (Yudhishthira), he reveals an eternal truth about the many paths by which beings are drawn to the Divine. He cites the famous verse:

“The Gopikas approached Kṛṣṇa through the intensity of their longing (Kāmōtkaṇṭhata);

Kaṁsa through fear;

Śiśupāla and other kings through enmity;

the Vṛṣṇis through kinship;

You, the Pāṇḍavas, through affection;

and we, the sages, through devotion.

Whichever way one relates to Him—whether in love, hatred, fear, or kinship—

all paths ultimately lead to Hari.”

Here, the GOAT poet Pothana beautifully emphasizes the subtle yet universal principle that any form of connection with the Divine (Śrī Kṛṣṇa) becomes a conduit for liberation. The emotional quality—whether passion, fear, or even hostility—is secondary; what truly matters is the focus of the mind upon the Lord. In every case, the consciousness is turned toward the Supreme, and in that very act of orientation lays the seed of liberation (moksha, freedom).

He then conveys this truth through a simple yet illuminating analogy: just as fire burns whoever touches it—whether a child, an adult, an elder, or a sage—the act of burning is intrinsic to the nature of fire. In the same way, liberation (uddharaṇa) is intrinsic to the nature of the Supreme Lord (Śrī Kṛṣṇa). Whoever comes into contact with Him, through any genuine form of engagement, is touched by His liberating essence.

However, this realization requires conscious redirection of the mind. The human mind must cling to something—either to the fleeting or to the eternal. If it is not anchored in the Divine, it becomes enslaved to worldly fascinations. Yet when turned toward the Lord, even ordinary life becomes sacred.

The Overhead Tank of Devotion

Pothana beautifully addresses a widespread misunderstanding—that turning one’s mind toward God means renouncing one’s family or worldly duties. He refutes this by using a vivid metaphor:

“In a household, there are many faucets—the sink, the washbasin, the shower. If water stops flowing, one doesn’t pour water into each faucet individually; but one fills the overhead tank, and all faucets flow naturally.”

Similarly, one need not abandon worldly responsibilities or affection for family. Rather, one should fill the inner reservoir of devotion to the Lord. When the heart is full of divine consciousness, that sacred awareness naturally flows into all relationships and duties. Every act, word, and thought becomes infused with spiritual grace.

Thus, Pothana’s wisdom bridges the divide between devotion and daily life. He reminds us that true spirituality is not escape from the world but elevation within it. Whatever be one’s temperament—whether that of the Gopika, the warrior, the enemy, or the sage—if one’s consciousness orbits around the Lord, one’s journey inevitably leads to liberation.

Likewise, one may live fully within saṁsāra—the world of family, relationships, and daily duties—without ever losing touch with the Divine. The scriptures repeatedly remind us that it is not renunciation of relationships, but sanctification of them, that leads one toward liberation.

Consider a man living happily with his wife. He may be deeply attached to her, cherish her affection, and find comfort in her companionship. There is nothing wrong in this love; yet he must never forget a single truth—that this relationship is a gift of His grace. He should inwardly feel, “It is by the compassion of Hari, Shiva or Goddess Lakshmi that I have been blessed with such a consort.” When this awareness remains alive in the heart, worldly affection is no longer bondage; it becomes worship.

Then life flows with quiet joy: “This wife, this loving companion who shares my life and sustains my lineage—she is none other than a manifestation of Lakshmi’s grace.” Likewise, the wife too may recognize that her husband and the harmony of their conjugal life are blessings born of the grace of Hari, Shiva, or Lakshmi themselves. To live with such understanding is to transform attachment into sanctified love.

Similarly, when a child achieves success—perhaps securing a fine education or a good career—the thought should arise: “It is the Lord who granted my child intelligence, health, and opportunity. This is His grace alone.” When you taste a delicious sweet, think: “Many in the world go hungry, yet the Lord has granted me this small joy. May I remember Him even in this sweetness.”

Such reflections keep the heart pure, anchored and centered. Every joy, every comfort, every success becomes a reminder of the Divine source from which all blessings flow. This conscious remembrance is like filling the overhead water tank—once it is full, every faucet in the house flows naturally. When the heart is filled with divine awareness, all relationships and actions in life flow effortlessly with sanctity.

Therefore, among all forms of attachment, the one rooted in love and devotion (Prema and Bhakti) is supreme. Other emotions—fear, hatred, or pride—may also lead one to the Lord, but they are paths filled with anguish. The way of enmity, as exemplified by Hiraṇyakaśipu or Śiśupāla, may indeed end at the Divine, yet the journey is one of torment. Every moment of such life burns like fire.

On the other hand, the life of devotion—Sāttvika Bhakti, pure and serene—brings peace to the devotee and grace to all who behold him. A heart filled with divine love radiates goodness, moral clarity, and joy. Such a person lives beautifully in this world and, upon leaving it, attains the supreme fortune of resting at the Lord’s lotus feet.

Krishna’s Accessible Forms

To cultivate this luminous devotion and to steady the mind in constant remembrance of the Supreme, one needs an anchor—a point of inner stillness, a sacred center of the heart where all thoughts and feelings converge into love for the Divine. That anchor is the living awareness that everything—joy, sorrow, relationship, and reward—is but the play of His grace.

If you have neither heard of the Divine, nor contemplated His form, and if you suddenly command your mind to “hold onto God,” how can it possibly comply? The mind cannot grasp the Infinite without an anchor, without a form or idea to which it can relate. For the mind to truly hold on, the Supreme must first descend into something graspable, something the human heart and imagination can approach. This is why the Lord, out of boundless compassion, manifests Himself in the most sulabha rūpa—the most accessible, intimate, and endearing forms.

Why else would the Infinite, who pervades the cosmos, choose to be born as a tender child in Gokula? Why would He run after cattle and calves, steal butter from the homes of the Gopikas, or allow Himself to be tied with a rope by Mother Yashoda? These līlās—the playful divine acts of Krishna—are not mere stories; they are windows through which the finite mind beholds the Infinite. Their deeper mysteries may be beyond our comprehension, but even the outer narrative, simple and sweet, holds the restless mind in its spell. The heart begins to dwell upon Krishna’s smile, His flute, His mischief, His tenderness—and in doing so, the mind slowly turns away from worldly anxieties and anchors itself in blissful contemplation.

And what happens then? Since the object of meditation is Krishna—He who is “Raso vai saha”, the very embodiment of divine bliss—the result is nothing less than profound peace and joy. The restless waves of thought settle into stillness. The heart, long parched by worldly pursuits, drinks deeply of divine nectar. This is why the Tenth Canto of the Śrīmad Bhāgavatam is called its very lifeblood—for it offers not abstract philosophy, but living, breathing intimacy with the Divine. It transforms devotion from a concept to an experience we all long for.

From Rama to Krishna: A Complete Spiritual Journey

As we enter the sacred Tenth Canto, Vyasa Bhagavan offers an elaborate portrayal of Krishna’s divine descent and His countless līlās—His childhood, His youth, His cosmic mission of dharma. The poet-saint Pothana, in his Telugu rendering, transmits this celestial narrative with both poetic brilliance and devotional depth. Yet, before we step into this Canto, Pothana draws our attention to a subtle parallel in the Navama Skandha (the Ninth Canto).

There, Pothana notes that since Lord Rama—the embodiment of dharma and ideal kingship—was born on Navami (the ninth lunar day), the Ninth Canto fittingly recounts the Rāmāyaṇa. The narrator in the Ninth Canto humbly mentions that he will not dwell extensively on the Rāmāyaṇa here, for it has already been heard by the listeners. However, he assures them that the grace earned through listening to the divine story of Rama in short is not lost—it is inherently woven into the Bhāgavatam itself. Thus, by reading Bhāgavatam – this very sacred discourse, the readers receive not only Krishna’s blessings but also the sanctifying grace of Śrī Rāmacandra Mūrti.

In this way, the Bhāgavatam becomes a complete spiritual journey—from the righteousness of Rama to the sweetness of Krishna, from moral perfection (Rama) to ecstatic devotion (Krishna). It carries the seeker step by step—from discipline to surrender, from understanding to union.

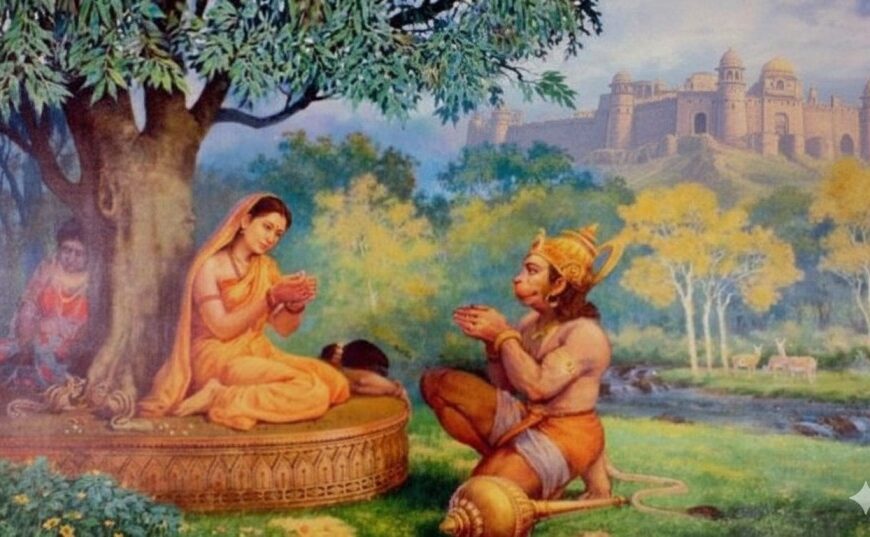

To briefly conclude the narrative of the Ninth Canto, Lord Rāmacandra—born in the illustrious Ikṣvāku dynasty to King Daśaratha after the sacred Putrakāmeṣṭi Yajña—was one of four divine sons and the very embodiment of dharma and virtue. To uphold His father’s solemn vow, He willingly embraced fourteen years of forest exile, accompanied by His devoted consort, Mother Sītā, and His loyal brother, Lakṣmaṇa. During this exile, He vanquished the forces of darkness, protected the sages and their sacrifices, and punished the demons who disturbed the sanctity of the forests.

When Rāvaṇa, the king of Laṅkā, abducted Sītā, Rāma allied with Sugrīva, overthrew the mighty Vāli, and with the tireless devotion of Hanumān, discovered Sītā held captive across the ocean. Gathering His divine army, He constructed the Setu (bridge) to Laṅkā, defeated Rāvaṇa and Kumbhakarṇa, and restored righteousness to the world. After reuniting with Sītā, Rāma ruled for eleven thousand years, establishing the golden age of Rāma Rājya, where justice, compassion, and prosperity prevailed.

This divine incarnation of the Lord revealed to humanity the highest standard of conduct, sacrifice, and righteousness. It was through the boundless grace of this very Rāma that the poet Pothana found inspiration to render the Bhāgavatam into Telugu. And it is the same eternal Rāma—now as Kṛṣṇa—who commands the next great chapter of divine play to unfold. For Rāma and Kṛṣṇa are not two but one, manifesting the same Supreme Reality through different līlās.

Thus, having traced the sacred arc of the Rāmāyaṇa, the stage is now set for the grand revelation of the Dashama Skandha, where the divine sweetness of Kṛṣṇa’s life awaits to be unveiled.