The Katha Upanishad, a profound ancient Hindu scripture, unveils a timeless dialogue between a young boy, intrepid seeker named Nachiketas and Yama, the Lord of Death. This narrative journey transcends cultural boundaries, offering universal insights into the nature of existence, the pursuit of truth, and the path to ultimate liberation. It is a story of courage, discernment, and the profound wisdom that lies beyond the veil of mortality, suitable for any global spiritual exploration.

Invocation

Original Transliteration and Translation:

Om ! May He protect us both together (by illumining the nature of knowledge).

May He sustain us both (by ensuring the fruits of knowledge).

May we attain the vigour (of knowledge) together.

Let what we learn enlighten us.

Let us not hate each other.

Om ! Peace ! Peace ! Peace !

Detailed Explanation:

This sacred invocation, resonating with the universal sound of Om, opens our journey into the depths of the Katha Upanishad. It is a heartfelt prayer, not just for personal enlightenment, but for a shared and harmonious pursuit of truth. “May He protect us both together” speaks to the divine guidance that shields both the teacher and the student, ensuring their joint exploration of profound knowledge. It implores the Supreme Reality to illuminate the very essence of understanding within their hearts. “May He sustain us both” extends this plea, asking that the fruits of their spiritual endeavor be preserved and that the wisdom gained nourishes their souls, providing strength and resilience on their path. The aspiration, “May we attain the vigour of knowledge together,” emphasizes a collective awakening of spiritual energy and intellectual fortitude, fostering a dynamic and insightful learning environment. “Let what we learn enlighten us” is a humble request for the knowledge to truly transform and illuminate their inner beings, moving beyond mere intellectual comprehension to deep, lived realization. Finally, “Let us not hate each other” underscores the foundational principle of unity and compassion, acknowledging that true spiritual progress flourishes in an atmosphere of mutual respect, empathy, and a complete absence of discord. The triple “Peace” (Shanti) at the conclusion signifies a profound wish for tranquility to pervade the body, mind, and spirit, extending to the entire universe, harmonizing all realms of existence.

Chapter One – Part One: The Encounter with Death

1-I-1. Original Transliteration and Translation:

Out of desire, so goes the story, the son of Vajasrava gave away all his wealth. He had a son named Nachiketas.

Detailed Explanation:

The ancient narrative unfolds with a pivotal scene: Vajasrava, a respected sage, embarked on a grand sacrificial ritual, intending to give away all his earthly possessions. However, the sacred text subtly reveals the underlying motive – this act of immense generosity was born not of pure, selfless devotion, but “out of desire,” a longing for specific rewards and merits in the afterlife. This subtle distinction between actions driven by genuine detachment and those propelled by personal gain sets the stage for the profound spiritual inquiry that follows. Into this context steps his son, Nachiketas, a young boy whose inherent purity and profound discernment would soon challenge the very conventions of his world.

1-I-2. Original Transliteration and Translation:

Though young, faith possessed him as presents were being brought; he thought:

Detailed Explanation:

Despite his tender years, Nachiketas possessed an extraordinary spiritual maturity. As the sacrificial offerings, intended for charitable distribution, were being prepared, a deep and unshakeable “faith” – not merely blind belief, but an intuitive sense of profound spiritual truth and righteousness – surged within him. This inner conviction prompted him to observe the proceedings with an acute and discerning eye, leading him to a crucial and uncomfortable realization about the true nature of his father’s gifts.

1-I-3. Original Transliteration and Translation:

Water has been drunk (for the last time by these cows), grass has been eaten (for the last time); they have yielded all their milk, and are devoid of (the power of) the organs. Those worlds are indeed joyless where he goes who offers these.

Detailed Explanation:

Nachiketas’s keen spiritual perception allowed him to see beyond the superficiality of the ritual. He observed that the cows his father intended to donate were decrepit and worn out: “Water has been drunk (for the last time by these cows), grass has been eaten (for the last time);” they were at the very end of their lives, their vitality depleted, having “yielded all their milk, and are devoid of (the power of) the organs.” This profound insight revealed a fundamental flaw in the sacrifice – the offerings were valueless, representing a mere formality rather than genuine generosity. With a wisdom far beyond his age, Nachiketas understood the karmic truth: “Those worlds are indeed joyless where he goes who offers these.” He realized that actions performed without true spirit, genuine selflessness, or qualitative worth, driven solely by a desire for personal gain, could only lead to insubstantial and unsatisfying outcomes, even in the realms beyond earthly existence.

1-I-4. Original Transliteration and Translation:

He then said to his parent, “father, to whom wilt thou give me?” A second time and a third time (he said it). To him he (the father) said, “To Death I give thee.”

Detailed Explanation:

Moved by his unwavering commitment to truth and righteousness, Nachiketas courageously confronted his father, asking a pointed question that aimed to expose the hypocrisy of the offerings: “Father, to whom wilt thou give me?” His inquiry implied a profound challenge: if his father was truly giving away everything of value, then surely, as his beloved son, Nachiketas himself should be part of that ultimate sacrifice. He repeated this question with persistent resolve, “A second time and a third time,” reflecting his unwavering determination to elicit an honest response. Provoked by his son’s challenging wisdom and his own underlying frustration, the father, in a fit of impulsive anger, declared, “To Death I give thee.” This dramatic pronouncement, born of irritation rather than intention, unexpectedly set Nachiketas on an extraordinary spiritual odyssey, directly to the very abode of Yama, the Lord of Death.

1-I-5. Original Transliteration and Translation:

Of many I go the first; of many I go the middle most. What purpose of Yama could there be which (my father) will get accomplished today through me?

Detailed Explanation:

Facing the formidable command to go to Death, Nachiketas reflected upon his fate with remarkable equanimity and philosophical depth, devoid of fear. He pondered his place within the vast tapestry of existence: “Of many I go the first; of many I go the middle most.” This could signify his humble acceptance of being either a pioneering spirit forging a new path, or simply one among the multitude destined for this ultimate journey. His mind, ever curious and discerning, immediately shifted from personal anxiety to a profound inquiry into the grand design: “What purpose of Yama could there be which (my father) will get accomplished today through me?” He sought to understand the deeper meaning behind this unexpected decree, recognizing that even an angry utterance could be a catalyst for a higher purpose, subtly hinting at the universal laws of cause and effect that govern all actions and their unfolding consequences.

1-I-6. Original Transliteration and Translation:

Think how your ancestors behaved; behold how others now behave. Like corn man decays, and like corn he is born again.

Detailed Explanation:

Before embarking on his fated journey to the realm of Death, Nachiketas, with the wisdom of an ancient sage encapsulated in a young boy, offered a final, profound piece of counsel, likely a silent reflection meant for his father or a universal truth for all who contemplate existence. He urged a contemplation of the timeless patterns of life: “Think how your ancestors behaved; behold how others now behave.” This was an invitation to recognize the enduring cycles of human conduct, morality, and spiritual aspiration across generations. He then delivered a powerful, universal truth about impermanence and renewal: “Like corn man decays, and like corn he is born again.” This poignant analogy illuminates the cyclical nature of birth, death, and rebirth (samsara), revealing that physical forms are transient, destined to wither, only to be renewed in new manifestations. It conveys the hopeful message that death is not an end, but a transformation, a continuous process of becoming, urging humanity to reflect on the deeper, unchanging essence that underlies this ceaseless flux.

1-I-7. Original Transliteration and Translation:

Like Vaisvanara (fire), a Brahmana guest enters the houses. Men offer this to propitiate him. O Vaivasvata (Yama): fetch water (for him).

Detailed Explanation:

Upon Nachiketas’s arrival at the dwelling of Yama, the Lord of Death, the profound reverence due to a spiritual guest is immediately emphasized. The sacred wisdom states that “Like Vaisvanara (fire), a Brahmana guest enters the houses.” This ancient maxim underscores the sanctity of a seeker of truth or a person of spiritual knowledge, likening their presence to the divine, purifying fire itself, which must be revered and honored. Yama, also known as Vaivasvata (son of Vivasvan, the Sun God), is thus prompted – either by his attendants or his own inherent understanding of cosmic law – to extend proper hospitality. The command to “fetch water (for him)” is not merely an act of refreshment but a sacred gesture of welcome and purification, acknowledging the grave implications of neglecting such a revered visitor.

1-I-8. Original Transliteration and Translation:

Hope, expectation, association with the effects (of these two), pleasant discourse, sacrifice, acts of pious liberality, sons and cattle – all these are destroyed in the case of the man of little intellect in whose house a Brahmana dwells without food.

Detailed Explanation:

This verse illuminates the severe karmic consequences of neglecting a sacred guest, particularly one embodying spiritual wisdom. Yama, understanding the gravity of his oversight in leaving Nachiketas unattended for three nights, reflects upon the dire implications. It is proclaimed that for an individual “of little intellect” – one lacking discernment and spiritual sensitivity – in whose home a person of spiritual caliber (a Brahmana) is allowed to remain without proper sustenance and respect, all blessings and meritorious accumulations can be irrevocably diminished. “Hope, expectation,” and “pleasant discourse” – the very fabric of positive social and mental well-being – crumble. Even the efficacy of “sacrifice” and “acts of pious liberality,” along with the prosperity symbolized by “sons and cattle,” are “destroyed.” This profound teaching extends beyond mere hospitality; it speaks to the universal law of karma, highlighting that genuine spiritual growth requires not only outward acts of merit but also an inner alignment of respect, wisdom, and an unwavering commitment to righteous conduct.

1-I-9. Original Transliteration and Translation:

O Brahmana, since thou, a worshipful guest, hast dwelt in my house for three nights without food, let me make salutation to thee. O Brahmana, may peace be with me. Therefore, ask for three boons in return.

Detailed Explanation:

Conscious of the profound transgression and its severe karmic repercussions, Yama, the venerable Lord of Death, humbly addresses Nachiketas, acknowledging his lapse in hospitality. “O Brahmana,” he begins, recognizing Nachiketas’s spiritual stature, “since thou, a worshipful guest, hast dwelt in my house for three nights without food, let me make salutation to thee.” This deferential greeting is an act of atonement, a sincere expression of reverence aimed at rectifying the error. His subsequent plea, “O Brahmana, may peace be with me,” reveals his deep concern for the cosmic harmony disturbed by his oversight. To fully compensate for the unintended suffering and ensure his own spiritual equilibrium, Yama then makes a profound offer: “Therefore, ask for three boons in return,” one for each night of neglect. This moment sets the stage for the unparalleled wisdom that Nachiketas will courageously seek and receive.

1-I-10. Original Transliteration and Translation:

O Death, let Gautama (my father) be relieved of the anxiety, let him become calm in mind and free from anger (towards me), and let him recognise me and talk to me when liberated by thee. Of the three boons, this is the first I choose.

Detailed Explanation:

Nachiketas, demonstrating a remarkable depth of compassion and filial piety, wastes no time in choosing his first boon. He does not ask for personal gain, wealth, or power, but instead prioritizes the emotional and spiritual well-being of his father. Addressing the Lord of Death, he humbly requests, “O Death, let Gautama (my father) be relieved of the anxiety” that must surely plague him after such a rash pronouncement. He desires his father to “become calm in mind and free from anger (towards me),” signifying a profound wish for reconciliation and the restoration of familial harmony, understanding that anger obscures true vision. Most importantly, he asks that his father “recognise me and talk to me when liberated by thee,” indicating a desire for recognition and acceptance upon his return from the realm of death, implying a deep understanding that spiritual peace often begins with the mending of human relationships. This selfless choice immediately establishes Nachiketas as a worthy recipient of higher spiritual wisdom.

1-I-11. Original Transliteration and Translation:

Ouddalaki, the son of Aruna, will recognise thee as before and will, with my permission, sleep peacefully during nights and on seeing thee released from the jaws of Death, he will be free from anger.

Detailed Explanation:

Yama, the Lord of Death, readily grants Nachiketas’s first compassionate boon, confirming its immediate fulfillment. He assures Nachiketas that his father, Uddalaka (also known as Aruni), “will recognise thee as before,” restoring the bond of father and son and erasing any lingering doubt or confusion. Furthermore, Yama decrees that Uddalaka “will, with my permission, sleep peacefully during nights,” signifying the removal of the anxiety and distress that would naturally accompany a parent’s rash action and the prolonged absence of his son. The ultimate peace for the father is promised upon Nachiketas’s return, as “on seeing thee released from the jaws of Death, he will be free from anger.” This swift and complete granting of the first boon underscores the divine approval of Nachiketas’s selfless virtue and establishes the stage for the deeper inquiries to come.

1-I-12. Original Transliteration and Translation:

There is no fear in heaven; nor art thou there; nor is there any fear from old age. Transcending both hunger and thirst and rising above grief, man rejoices in heaven.

Detailed Explanation:

In preparing to articulate his second boon, Nachiketas describes the allure of the celestial realms, often referred to as ‘heaven’ (Svarga). He paints a picture of a place utterly devoid of the anxieties and sufferings that plague human existence: “There is no fear in heaven; nor art thou there,” he addresses Yama, implying that the very presence of Death, the ultimate fear-inducer, is absent. He highlights the absence of the decay of time, stating, “nor is there any fear from old age.” Furthermore, the inhabitants of these blissful realms are liberated from fundamental physical discomforts: “Transcending both hunger and thirst.” Crucially, they also rise “above grief,” suggesting a state of pure contentment and joy. In such a place, “man rejoices in heaven.” While a state of profound bliss, this description still implies a temporary dwelling within the cycle of existence, setting the stage for a boon that seeks understanding of this exalted, yet not ultimate, reality.

1-I-13. Original Transliteration and Translation:

O Death, thou knowest the Fire that leads to heaven. Instruct me, who am endowed with faith, about that (Fire) by which those who dwell in heaven attain immortality. This I choose for my second boon.

Detailed Explanation:

Having set the scene of heavenly bliss, Nachiketas articulates his second profound request. He turns to Yama, acknowledging Death’s unique knowledge: “O Death, thou knowest the Fire that leads to heaven.” This refers to the sacred Nachiketa Fire, a specific sacrificial ritual believed to grant access to the higher celestial planes and a prolonged, joyful existence there – a form of ‘immortality’ within the cycle of samsara, rather than ultimate liberation. Nachiketas expresses his profound readiness to learn, stating, “Instruct me, who am endowed with faith,” emphasizing that his inquiry stems from a deep inner conviction and sincerity (shraddha), not mere curiosity. He specifically seeks to understand the precise nature of “that (Fire) by which those who dwell in heaven attain immortality,” indicating his desire for the wisdom that secures such a blissful, albeit still temporary, state. With clear resolve, he declares, “This I choose for my second boon.”

1-I-14. Original Transliteration and Translation:

I will teach thee well; listen to me and understand, O Nachiketas, I know the Fire that leads to heaven. Know that Fire which is the means for the attainment of heaven and which is the support (of the universe) and located in the cavity.

Detailed Explanation:

Yama, pleased by Nachiketas’s earnestness and his choice to seek knowledge, readily agrees to impart this esoteric wisdom. “I will teach thee well,” he affirms, inviting Nachiketas to engage with utmost attentiveness: “listen to me and understand, O Nachiketas.” Yama confirms his mastery of this sacred knowledge: “I know the Fire that leads to heaven.” He then reveals a deeper aspect of this ‘Fire,’ hinting at its cosmic significance beyond mere ritual. He instructs Nachiketas to “Know that Fire which is the means for the attainment of heaven and which is the support (of the universe) and located in the cavity.” This suggests that the Nachiketa Fire is not just an external ritual but also an inner principle—a fundamental force that underpins the cosmos and can be realized within the deepest chamber of one’s own being, the heart or intellect. This dual understanding paves the way for a more profound spiritual revelation.

1-I-15. Original Transliteration and Translation:

Death told him of the Fire, the source of the worlds, the sort of bricks (for raising the sacrificial altar), how many, and how (to kindle the fire) and he (Nachiketas) too repeated it as it was told. Then Death, becoming delighted over it, said again:

Detailed Explanation:

True to his word, Yama meticulously imparted the intricate knowledge of the Nachiketa Fire to the young seeker. He delved into its profound cosmic significance, explaining it as “the source of the worlds,” implying its foundational role in manifestation. He then detailed the practical aspects of its ritualistic construction: “the sort of bricks (for raising the sacrificial altar), how many, and how (to kindle the fire).” Nachiketas, demonstrating an extraordinary capacity for absorption and intellectual precision, absorbed every detail and “repeated it as it was told,” flawlessly reciting the complex instructions. Witnessing such remarkable receptivity and accurate comprehension from his student, Yama was filled with profound satisfaction and delight, signifying the joy of a true guru discovering a supremely worthy disciple.

1-I-16. Original Transliteration and Translation:

The exalted one, being pleased, said to him: “I grant thee again another boon now. By thy name itself shall this fire be known; and accept thou this necklace of manifold forms”.

Detailed Explanation:

Yama, now profoundly impressed and uplifted by Nachiketas’s exceptional grasp of the sacred knowledge, extended an additional, spontaneous blessing. “The exalted one, being pleased,” he said to the young seeker, “I grant thee again another boon now.” As a testament to Nachiketas’s brilliance and diligence, Yama decreed a lasting legacy: “By thy name itself shall this fire be known,” ensuring that the Nachiketa Fire would forever carry his name, immortalizing his contribution to spiritual wisdom. Furthermore, Yama offered a tangible symbol of his approval and the profound fruits of such knowledge: “and accept thou this necklace of manifold forms.” This necklace could symbolize the diverse rewards of performing the ritual, the various forms of knowledge attained, or even the myriad manifestations of the universe itself, indicating a deep spiritual gift of understanding and prosperity.

1-I-17. Original Transliteration and Translation:

Whoso kindles the Nachiketas fire thrice and becomes united with the three and does the three-fold karma, transcends birth and death. Knowing the omniscient one, born of Brahma, bright and adorable, and realizing it, he attains to surpassing peace.

Detailed Explanation:

Yama further elucidated the profound benefits accessible to one who diligently and with full understanding engages with the Nachiketa Fire. He explained that “Whoso kindles the Nachiketas fire thrice” – signifying perfect completion and mastery of the ritual, perhaps also implying a deep integration of body, mind, and spirit – and “becomes united with the three” (often interpreted as the three Vedas, the three forms of Agni, or the triple nature of reality: waking, dreaming, and deep sleep) and “does the three-fold karma” (referring to actions performed with body, speech, and mind, or perhaps specific ritualistic actions), such an individual “transcends birth and death.” In this context, ‘transcending birth and death’ implies attaining a prolonged, highly blissful existence in the celestial realms, moving beyond the immediate cycle of earthly suffering, rather than ultimate liberation from all existence. Moreover, by “Knowing the omniscient one,” referring to Hiranyagarbha or Prajapati, the cosmic intelligence “born of Brahma, bright and adorable,” and truly “realizing it,” such a seeker “attains to surpassing peace.” This peace is a profound tranquility, a state of deep spiritual contentment found within the higher cosmic order, a significant step on the ladder of spiritual ascent.

1-I-18. Original Transliteration and Translation:

He who, knowing the three (form of brick etc.,), piles up the Nachiketa Fire with this knowledge, throws off the chains of death even before (the body falls off), and rising over grief, rejoices in heaven.

Detailed Explanation:

This verse reinforces the transformative power of engaging with the Nachiketa Fire, emphasizing that true mastery comes from understanding its underlying principles, not just mechanical adherence to ritual. The one “who, knowing the three (form of brick etc.,)” – understanding the precise sacred measurements and forms for constructing the altar – and meticulously “piles up the Nachiketa Fire with this knowledge,” demonstrates a profound integration of wisdom and action. Such an individual, through this elevated practice, “throws off the chains of death even before (the body falls off).” This remarkable phrase suggests a liberation from the psychological and spiritual bondage of mortality and the fear of death, experienced even while still in human form. By transcending these earthly limitations, the practitioner finds themselves “rising over grief” and experiencing a profound, anticipatory “rejoice[ing] in heaven.” It paints a picture of a soul already tasting the joy of higher realms, even prior to physical dissolution, due to their enlightened understanding and practice.

1-I-19. Original Transliteration and Translation:

This is the Fire, O Nachiketas, which leads to heaven and which thou hast chosen for the second boon. Of this Fire, people will speak as thine indeed. O Nachiketas, choose the third boon.

Detailed Explanation:

With the teaching and granting of the second boon complete, Yama consolidates the understanding, affirming the efficacy of the knowledge just imparted. He explicitly states, “This is the Fire, O Nachiketas, which leads to heaven and which thou hast chosen for the second boon.” He reiterates the lasting recognition Nachiketas has earned, confirming that “Of this Fire, people will speak as thine indeed,” ensuring his name will forever be associated with this sacred wisdom. Having fulfilled both of Nachiketas’s requests for his father’s peace and for the means to attain heavenly bliss, Yama then prompts the young seeker for the ultimate inquiry, inviting him to delve into the deepest mysteries of existence: “O Nachiketas, choose the third boon.” This invitation sets the stage for the core philosophical teachings of the Upanishad, moving beyond temporal rewards to eternal truth.

1-I-20. Original Transliteration and Translation:

This doubt as to what happens to a man after death – some say he is, and some others say he is not, – I shall know being taught by thee. Of the boons, this is the third boon.

Detailed Explanation:

With unwavering resolve, Nachiketas articulates his most profound and pivotal request, the very heart of his spiritual quest. He seeks knowledge regarding the ultimate mystery that has puzzled humanity throughout time: “This doubt as to what happens to a man after death – some say he is, and some others say he is not.” This acknowledges the universal human uncertainty surrounding the soul’s fate, the question of existence beyond the physical body. Nachiketas, facing Death itself, declares his unyielding desire to resolve this fundamental existential enigma, stating with conviction, “I shall know being taught by thee,” recognizing Yama as the sole authority on this profound subject. With absolute clarity, he asserts, “Of the boons, this is the third boon,” cementing his commitment to seek only this highest wisdom, transcending all lesser desires.

1-I-21. Original Transliteration and Translation:

Even by the gods this doubt was entertained in days of yore. This topic, being subtle, is not easy to comprehend. Ask for some other boon, O Nachiketas. Don’t press me; give up this (boon) for me.

Detailed Explanation:

Faced with Nachiketas’s audacious and profound request, Yama, the Lord of Death, initially attempts to dissuade him. He underscores the immense difficulty and esoteric nature of this ultimate knowledge, revealing its profundity by stating, “Even by the gods this doubt was entertained in days of yore.” This implies that even celestial beings, far superior to humans, have grappled with this same existential question, highlighting its extraordinary subtlety and elusiveness. “This topic, being subtle, is not easy to comprehend,” Yama cautions, testing Nachiketas’s sincerity and readiness for such a deep revelation. He urges Nachiketas to reconsider, pleading, “Ask for some other boon, O Nachiketas. Don’t press me; give up this (boon) for me.” This reluctance is a classical spiritual test, designed to ascertain the seeker’s true commitment, discrimination, and capacity to receive the highest wisdom.

1-I-22. Original Transliteration and Translation:

(Nachiketas said:) Since even by the gods was doubt entertained in this regard and (since) thou sayest, O Death, that this is not easily comprehended, no other preceptor like thee can be had to instruct on this nor is there any other boon equal to this.

Detailed Explanation:

Nachiketas, demonstrating unparalleled wisdom and unwavering resolve, skillfully turns Yama’s own words into a powerful affirmation of his request. He reasons, “Since even by the gods was doubt entertained in this regard and (since) thou sayest, O Death, that this is not easily comprehended,” then this very difficulty underscores its supreme value and the unique qualification of Yama as its teacher. He passionately asserts, “no other preceptor like thee can be had to instruct on this,” recognizing that the Lord of Death, who embodies the ultimate truth of transition, is the only authority capable of revealing such a profound secret. Further solidifying his choice, Nachiketas declares, “nor is there any other boon equal to this,” emphasizing that no worldly or heavenly pleasure can compare to the ultimate knowledge of what lies beyond death. This resolute stand confirms Nachiketas’s readiness for the highest spiritual wisdom, proving his discrimination and single-minded dedication.

1-I-23. Original Transliteration and Translation:

Ask for sons and grandsons who will live a hundred years. Ask for herds of cattle, elephants gold and horses, as also for a vast extent of earth and thyself live for as many autumns as thou desirest.

Detailed Explanation:

Undeterred by Nachiketas’s steadfastness, Yama escalates his attempts to sway the young seeker, offering a plethora of worldly attractions. He tempts Nachiketas with the promise of deep familial continuity and prosperity: “Ask for sons and grandsons who will live a hundred years,” assuring a long and flourishing lineage. He then offers immense material wealth and dominion: “Ask for herds of cattle, elephants, gold and horses, as also for a vast extent of earth,” painting a picture of unparalleled affluence and power. Finally, Yama extends the ultimate earthly temptation: “and thyself live for as many autumns as thou desirest,” offering boundless longevity. This barrage of offerings represents the peak of human ambition and desire, a profound test designed to reveal whether Nachiketas’s spiritual resolve could be fractured by the allure of the temporal.

1-I-24. Original Transliteration and Translation:

If thou thinkest any other boon to be equal to this, ask for wealth and longevity. Be thou the ruler over a vast country, O Nachiketas; I shall make thee enjoy all thy longings.

Detailed Explanation:

Yama continues his formidable challenge, pressing Nachiketas further by reiterating the immense scope of the worldly pleasures at his disposal. He encourages the young seeker, “If thou thinkest any other boon to be equal to this, ask for wealth and longevity,” implying that there are no limits to the material and temporal gifts he could bestow. To sweeten the offer, Yama expands the vision of power: “Be thou the ruler over a vast country, O Nachiketas,” promising absolute dominion and unparalleled influence. With an assurance of complete gratification, he declares, “I shall make thee enjoy all thy longings,” aiming to entice Nachiketas with the complete fulfillment of every conceivable earthly desire. This continued testing underscores the pervasive allure of worldly life and sets the stage for Nachiketas’s profound rejection.

1-I-25. Original Transliteration and Translation:

What all things there are in the human world which are desirable, but hard to win, pray for all those desirable things according to thy pleasure. Here are these damsels with the chariots and lutes, the like of whom can never be had by men. By them, given by me, get thy services rendered, O Nachiketas, do not ask about death.

Detailed Explanation:

In a final, ultimate test of Nachiketas’s detachment, Yama offers the pinnacle of sensory and aesthetic delights that are “desirable, but hard to win” in the human realm. He grants complete freedom to choose any longed-for pleasure: “pray for all those desirable things according to thy pleasure.” Yama then presents the most exquisite forms of temptation: “Here are these damsels with the chariots and lutes, the like of whom can never be had by men.” These celestial beauties, embodying ultimate charm and skilled in music and art, are offered to serve Nachiketas, promising unparalleled comfort and entertainment. Yama explicitly states, “By them, given by me, get thy services rendered, O Nachiketas,” making the offer undeniably real and tempting. The very last instruction reveals the true purpose of this barrage of desires: “do not ask about death.” This direct plea attempts to divert Nachiketas from his ultimate spiritual inquiry, highlighting the profound conflict between transient pleasures and the eternal truth.

1-I-26. Original Transliteration and Translation:

These, O Death, are ephemeral and they tend to wear out the vigour of all the senses of man. Even the whole life is short indeed. Be thine alone the chariots; be thine the dance and music.

Detailed Explanation:

Nachiketas, with a spiritual maturity that transcends the allure of fleeting pleasures, firmly rejects Yama’s grand temptations. Addressing Death directly, he articulates a profound universal truth: “These, O Death, are ephemeral,” recognizing the transient nature of all worldly enjoyments. He insightfully observes that such temporary delights “tend to wear out the vigour of all the senses of man,” implying that chasing external gratifications ultimately depletes one’s inner vitality and distracts from true purpose. He further underscores the brevity of human existence, stating, “Even the whole life is short indeed.” With remarkable detachment, he hands back the very objects of temptation: “Be thine alone the chariots; be thine the dance and music.” This courageous rejection powerfully demonstrates his discrimination (viveka) between the fleeting and the eternal, proving his unwavering commitment to the ultimate truth over all forms of sensory gratification.

1-I-27. Original Transliteration and Translation:

Man cannot be satisfied with wealth. If we need wealth, we shall get it if we only see thee. We shall live until such time as thou wilt rule. But the boon to be asked for (by me) is that alone.

Detailed Explanation:

Nachiketas continues his profound refutation, exposing the inherent futility of material pursuits. He asserts a universal truth: “Man cannot be satisfied with wealth,” recognizing the insatiable nature of desires that endlessly crave more, never finding true contentment in accumulation. With remarkable spiritual insight, he then cleverly turns the tables on Yama, suggesting that true abundance comes from a higher source: “If we need wealth, we shall get it if we only see thee.” This implies that contact with the supreme power (Yama, as a cosmic principle, or Brahman, which Yama represents) inherently bestows all necessary provisions, making direct pursuit of wealth unnecessary and distracting. He also addresses the offer of longevity, stating, “We shall live until such time as thou wilt rule,” acknowledging that the span of life is subject to cosmic law. However, he then brings the conversation back to his singular, unyielding purpose: “But the boon to be asked for (by me) is that alone,” reinforcing his absolute commitment to the knowledge of what lies beyond death, above all other considerations.

1-I-28. Original Transliteration and Translation:

Having gained contact with the undecaying and the immortal, what decaying mortal dwelling on the earth below who knows the higher goal, will delight in long life, after becoming aware of the (transitoriness of) beauty (Varian) and sport (rati) and the joy (pramoda) thereof.

Detailed Explanation:

Nachiketas poses a powerful rhetorical question, revealing the depth of his spiritual discernment. He implies that for any discerning being who has even fleetingly “gained contact with the undecaying and the immortal” – the eternal, unchanging truth – the allure of transient worldly pleasures pales into insignificance. He questions: “what decaying mortal dwelling on the earth below who knows the higher goal, will delight in long life,” especially when such a life is merely an extension of fleeting experiences? Having become acutely “aware of the (transitoriness of) beauty (Varian) and sport (rati) and the joy (pramoda) thereof,” the true seeker recognizes that all earthly delights are subject to decay and dissolution. This profound insight underscores that true wisdom inspires one to transcend the desire for extended temporal existence, as it cannot compare to the infinite, unchanging bliss of the eternal Self.

1-I-29. Original Transliteration and Translation:

O Death, tell us of that, of the great Beyond, about which man entertain doubt. Nachiketas does not pray for any other boon than this which enters into the secret that is hidden.

Detailed Explanation:

With an unwavering and final plea, Nachiketas reiterates his singular and profound request, leaving no room for further worldly diversion. Addressing Yama directly, he implores, “O Death, tell us of that, of the great Beyond, about which man entertains doubt.” This underscores the universal human yearning to comprehend the ultimate reality, the nature of consciousness, and existence beyond the veil of physical death. Nachiketas firmly declares his absolute commitment to this ultimate truth: “Nachiketas does not pray for any other boon than this which enters into the secret that is hidden.” This statement beautifully encapsulates the essence of true spiritual aspiration – a courageous and single-pointed pursuit of the deepest, most concealed wisdom, rejecting all lesser gratifications for the sake of ultimate liberation and understanding. His resolve now complete, Yama is ready to impart the highest knowledge.

Chapter One – Part Two: The Path of Wisdom

1-II-1. Original Transliteration and Translation:

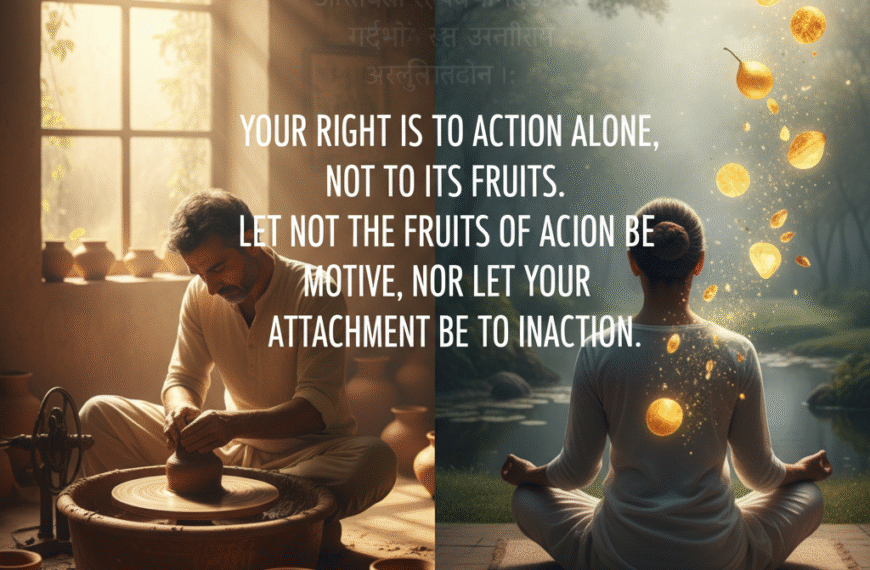

Different is (that which is) preferable; and different, indeed, is the pleasurable. These two, serving different purposes, blind man. Good accrues to him who, of these two, chooses the preferable. He who chooses the pleasurable falls from the goal.

Detailed Explanation:

Yama, now assured of Nachiketas’s readiness, begins his profound teaching by introducing a fundamental dichotomy that defines the human spiritual journey. He states that “Different is (that which is) preferable (Shreyas); and different, indeed, is the pleasurable (Preyas).” These two paths, though both enticing, serve distinctly different purposes in life and lead to vastly divergent destinies. The path of the pleasurable, while immediately gratifying to the senses and ego, ultimately “blind[s] man” to higher truths, trapping them in endless cycles of desire and dissatisfaction. In contrast, the path of the preferable, though often challenging and requiring self-discipline, leads to enduring spiritual growth and ultimate well-being. Yama unequivocally declares, “Good accrues to him who, of these two, chooses the preferable,” highlighting the immense benefits of wise discernment. Conversely, “He who chooses the pleasurable falls from the goal,” meaning they deviate from the ultimate purpose of human existence, which is self-realization and liberation. This foundational insight serves as a universal compass for ethical and spiritual navigation.

1-II-2. Original Transliteration and Translation:

The preferable and the pleasurable approach man. The intelligent one examines both and separates them. Yea, the intelligent one prefers the preferable to the pleasurable, (whereas) the ignorant one selects the pleasurable for the sake of yoga (attainment of that which is not already possessed) and kshema (the preservation of that which is already in possession).

Detailed Explanation:

Building upon the distinction between the preferable (Shreyas) and the pleasurable (Preyas), Yama elaborates on how these two paths invariably “approach man,” presenting themselves as choices in every moment of life. The truly “intelligent one,” possessed of spiritual discrimination (viveka), does not blindly follow impulse. Instead, they “examines both and separates them,” consciously discerning their true nature and long-term consequences. Such a wise individual, through keen insight, “prefers the preferable to the pleasurable,” prioritizing enduring spiritual well-being over fleeting sensory gratification. In stark contrast, “the ignorant one,” lacking this profound discernment, invariably “selects the pleasurable for the sake of yoga (attainment of that which is not already possessed) and kshema (the preservation of that which is already in possession).” This reveals that the unilluminated mind seeks pleasure for the accumulation of possessions and their security, binding themselves further to the transient world, while the wise seek the eternal.

1-II-3. Original Transliteration and Translation:

Thou hast relinquished, O Nachiketas, all objects of desire, dear and of covetable nature, pondering over their worthlessness. Thou hast not accepted the path of wealth in which perish many a mortal.

Detailed Explanation:

Yama then commends Nachiketas, affirming his extraordinary spiritual maturity and the correctness of his choice. “Thou hast relinquished, O Nachiketas, all objects of desire, dear and of covetable nature,” he praises, acknowledging the immense allure of the worldly treasures, power, and pleasures that Nachiketas so resolutely refused. This profound act of renunciation was not a whimsical decision but a deeply informed one, for Nachiketas had wisely engaged in “pondering over their worthlessness.” His discerning mind perceived the inherent transience and ultimate emptiness of all material pursuits. Yama further emphasizes this wisdom by stating, “Thou hast not accepted the path of wealth in which perish many a mortal,” highlighting how countless lives are consumed by the relentless pursuit of material accumulation, ultimately leading to spiritual disillusionment and decay. This recognition of Nachiketas’s discrimination reinforces the essential prerequisite for attaining the highest knowledge.

1-II-4. Original Transliteration and Translation:

What is known as ignorance and what is known as knowledge are highly opposed (to each other), and lead to different ways. I consider Nachiketas to be aspiring after knowledge, for desires, numerous though they be, did not tear thee away.

Detailed Explanation:

Yama further elucidates the stark dichotomy between avidya (ignorance) and vidya (knowledge), portraying them as fundamentally “highly opposed (to each other),” leading to profoundly “different ways” of existence and destiny. Ignorance binds one to the cycle of suffering, while true knowledge liberates. Yama then profoundly affirms Nachiketas’s true nature, recognizing his unwavering commitment to liberation: “I consider Nachiketas to be aspiring after knowledge,” for despite the intense and “numerous though they be” temptations of desire presented to him, these fleeting allurements “did not tear thee away” from his chosen path. This statement not only praises Nachiketas’s exceptional resolve but also sets the stage for the central teaching, emphasizing that genuine spiritual aspiration is marked by an unshakeable focus, unswayed by the distractions of the material world.

1-II-5. Original Transliteration and Translation:

Living in the midst of ignorance and deeming themselves intelligent and enlightened, the ignorant go round and round staggering in crooked paths, like the blind led by the blind.

Detailed Explanation:

This verse paints a vivid and poignant picture of spiritual delusion. Yama warns of the plight of those who, “Living in the midst of ignorance,” remain oblivious to their true state. Worse still, these individuals often “deeming themselves intelligent and enlightened,” fall into the trap of spiritual arrogance, mistaking superficial understanding for profound wisdom. Consequently, “the ignorant go round and round staggering in crooked paths,” endlessly wandering through cycles of confusion, suffering, and rebirth, unable to find genuine direction or peace. The powerful simile, “like the blind led by the blind,” vividly illustrates the futility and danger of following those who themselves are spiritually unseeing, emphasizing the critical importance of true spiritual insight and authentic guidance on the path to liberation.

1-II-6. Original Transliteration and Translation:

The means of attaining the other world does not become revealed to the non-discriminating one who, deluded by wealth, has become negligent. He who thinks, ‘this world alone is and none else’ comes to my thraldom again and again.

Detailed Explanation:

Yama explains why the deepest spiritual truths remain hidden from so many. “The means of attaining the other world,” the path to higher states of consciousness or liberation, “does not become revealed to the non-discriminating one,” the individual lacking the crucial capacity for discernment (viveka). This spiritual blindness is often exacerbated by worldly attachments: “who, deluded by wealth, has become negligent” of the deeper realities. Such individuals, whose minds are consumed by material pursuits, mistakenly believe that “this world alone is and none else,” denying any reality beyond the immediate sensory experience. Yama, as the Lord of Death, then delivers a stark consequence: such a soul “comes to my thraldom again and again,” trapped in the endless cycle of birth, death, and rebirth (samsara), unable to break free from the realm of impermanence due to their material attachments and spiritual shortsightedness.

1-II-7. Original Transliteration and Translation:

Of the Self many are not even able to hear; Him many, though they hear, do not comprehend. Wonderful is the expounder of the Self and attainer, proficient. The knower (of the Self) taught by an able preceptor is wonderful.

Detailed Explanation:

This profound verse speaks to the extraordinary rarity and subtlety of Self-realization, highlighting the arduous journey of spiritual awakening. Yama observes that “Of the Self many are not even able to hear,” implying that for countless beings, the very concept of an eternal, inner essence remains entirely inaccessible or unheard of. Even among those who do encounter the teaching, “many, though they hear, do not comprehend” its profound truth, struggling to grasp its ineffable nature. Consequently, “Wonderful is the expounder of the Self and attainer, proficient,” acknowledging the rarity and immense spiritual merit of one who can genuinely articulate and, more importantly, realize this ultimate truth. The verse culminates by praising the most fortunate of seekers: “The knower (of the Self) taught by an able preceptor is wonderful,” emphasizing the invaluable role of an enlightened spiritual guide in leading a disciple to direct, transformative experience.

1-II-8. Original Transliteration and Translation:

This (Self), if taught by an inferior person, is not easily comprehended, for It is variously thought of. Unless taught by another (who is a perceiver of non-difference) there is no way (of comprehending It), for It is not arguable and is subtler than subtlety.

Detailed Explanation:

Yama continues to emphasize the profound difficulty in apprehending the true Self, underscoring the indispensable role of an authentic spiritual guide. He warns that if this ultimate truth is “taught by an inferior person” – one who has not directly experienced it – “It is not easily comprehended, for It is variously thought of,” leading to confusion and misinterpretation. Intellectual debates or philosophical arguments alone are insufficient. “Unless taught by another (who is a perceiver of non-difference)” – a rare soul who has realized the indivisible unity of the Self with Brahman – “there is no way (of comprehending It).” This is because the Self transcends conventional logic and intellectual discourse; “It is not arguable,” meaning it cannot be grasped through mere debate or reasoning. Its nature is so incredibly refined and elusive that “It is subtler than subtlety,” requiring an intuitive, direct perception fostered by a realized master.

1-II-9. Original Transliteration and Translation:

This (knowledge of the Self) attained by thee cannot be had through argumentation. O dearest, this doctrine, only if taught by some teacher (other than a logician), leads to right knowledge. O, thou art rooted in truth. May a questioner be ever like thee, O Nachiketas.

Detailed Explanation:

Yama concludes his assessment of the prerequisites for Self-knowledge by reiterating the limitations of intellectual inquiry alone, while simultaneously offering profound praise to Nachiketas. He states, “This (knowledge of the Self) attained by thee cannot be had through argumentation,” confirming that mere logic, debate, or scholarly discourse is insufficient for grasping the ultimate truth. “O dearest,” he lovingly addresses Nachiketas, emphasizing that “this doctrine, only if taught by some teacher (other than a logician), leads to right knowledge.” This underscores the necessity of a realized teacher, one who transmits truth through direct experience and insight, not just intellectual constructs. Overjoyed by Nachiketas’s steadfastness and sincere aspiration, Yama proclaims, “O, thou art rooted in truth.” His final benediction expresses a universal aspiration for all seekers: “May a questioner be ever like thee, O Nachiketas,” acknowledging that Nachiketas embodies the ideal qualities of spiritual earnestness, discernment, and unwavering dedication required for the profound journey of self-discovery.

1-II-10. Original Transliteration and Translation:

I know that the treasure is impermanent, for that which is constant cannot be reached by things which are not constant. Therefore, has the Nachiketa Fire been kindled by me with impermanent things, and I have attained the eternal.

Detailed Explanation:

Yama offers a glimpse into his own profound wisdom and the path he traversed to reach his elevated state. He declares, “I know that the treasure is impermanent,” recognizing the inherent transience of all material accumulations and worldly achievements. He then articulates a fundamental spiritual principle: “for that which is constant cannot be reached by things which are not constant.” This means that the eternal and unchanging reality (Brahman) cannot be grasped or attained through perishable, temporary means. Yet, Yama reveals a paradox in his own journey: “Therefore, has the Nachiketa Fire been kindled by me with impermanent things.” This refers to his diligent performance of rituals using material offerings. However, his profound understanding transformed the ritual: “and I have attained the eternal.” This suggests that even through practices involving transient elements, when undertaken with profound knowledge, selfless intention, and deep spiritual insight, one can transcend the limitations of the impermanent and realize the ultimate, unchanging truth. His own experience serves as a testament to the transformative power of spiritual wisdom.

1-II-11. Original Transliteration and Translation:

The fulfilment of all desires, the support of the universe, the endless fruits of sacrifice, the other shore of fearlessness, the extensive path which is praiseworthy and great, as also (thy own exalted) state – seeing all these thou hast, intelligent as thou art, boldly rejected (them).

Detailed Explanation:

Yama, in a sweeping commendation, marvels at Nachiketas’s extraordinary discernment and unwavering focus on the ultimate truth. He enumerates the vast and alluring spectrum of rewards that Nachiketas has resolutely turned away from: “The fulfilment of all desires,” encompassing every conceivable worldly longing; “the support of the universe,” implying cosmic power or influence; “the endless fruits of sacrifice,” representing immense karmic merit in celestial realms; “the other shore of fearlessness,” a state of profound security beyond earthly anxieties; and “the extensive path which is praiseworthy and great,” referring to the highly esteemed conventional paths to prosperity and renown. Even Yama’s own “exalted state” of power and wisdom, which he implicitly offered, was gracefully declined. Yama concludes by emphasizing Nachiketas’s unique insight: “seeing all these thou hast, intelligent as thou art, boldly rejected (them).” This highlights Nachiketas’s supreme intelligence and spiritual courage in prioritizing the eternal over all forms of fleeting glory, demonstrating his exceptional readiness for the deepest revelation.

1-II-12. Original Transliteration and Translation:

The intelligent one, knowing through concentration of mind the Self that is hard to perceive, lodged in the innermost recess, located in intelligence, seated amidst misery, and ancient, abandons joy and grief.

Detailed Explanation:

Yama now delves into the nature of Self-realization, explaining how the truly “intelligent one” achieves it. This profound understanding comes “through concentration of mind,” a focused and disciplined introspection that leads to the realization of the Self. This Self is described as “hard to perceive” because it is subtle and lies beyond ordinary sensory or intellectual grasp. It is “lodged in the innermost recess” of one’s being, the deepest chamber of the heart or consciousness, and is “located in intelligence,” meaning it is the very essence of discerning awareness. Paradoxically, while inherently pure, it appears “seated amidst misery” due to its identification with the transient body and mind, which are subject to suffering. This Self is also “ancient,” eternal and primordial. The profound outcome of this realization is liberation from the dualities of human experience: the awakened individual “abandons joy and grief,” transcending the fluctuating emotions of worldly existence and dwelling in an unshakable state of peace.

1-II-13. Original Transliteration and Translation:

Having heard this and grasped it well, the mortal, separating the virtuous being (from the body etc.,) and attaining this subtle Self, rejoices having obtained that which causes joy. The abode (of Brahman), I think, is wide open unto Nachiketas.

Detailed Explanation:

Yama describes the transformative power of grasping the profound truth of the Self. When a mortal, “Having heard this and grasped it well” – meaning not just intellectually but with deep intuitive understanding – proceeds to undertake the crucial spiritual work of “separating the virtuous being (from the body etc.)” by realizing that the true Self is distinct from the perishable physical form, mind, and senses, then by “attaining this subtle Self,” they discover an unparalleled source of inner fulfillment. Such a liberated soul “rejoices having obtained that which causes joy,” realizing that the ultimate source of happiness lies within, not in external transient pleasures. Yama, seeing Nachiketas’s exceptional readiness and purity, concludes with a profound declaration of affirmation: “The abode (of Brahman), I think, is wide open unto Nachiketas,” signifying that the path to ultimate reality, to union with the Divine, is clear and accessible for him.

1-II-14. Original Transliteration and Translation:

Tell me of that which thou seest as distinct from virtue, distinct from vice, distinct from effect and cause, distinct from the past and the future.

Detailed Explanation:

Nachiketas, having absorbed the initial profound teachings, now refines his inquiry, expressing his desire for the ultimate, unconditioned truth. He asks Yama to reveal “that which thou seest as distinct from virtue, distinct from vice,” signifying a reality beyond the conventional moral dualities of good and evil, which are relative to human experience. He seeks that which is “distinct from effect and cause,” a primordial source that transcends the entire chain of phenomenal existence and causality. Furthermore, he asks for that which is “distinct from the past and the future,” indicating a timeless, eternal reality that lies beyond the confines of linear temporal experience. This precise and profound question is an inquiry into the nature of Nirguna Brahman, the formless, attributeless, absolute Reality, which is the ultimate goal of Upanishadic wisdom.

1-II-15. Original Transliteration and Translation:

The goal which all the Vedas expound, which all austerities declare, and desiring which aspirants resort to Brahmacharya, that goal, I tell thee briefly: It is this – Om.

Detailed Explanation:

Responding to Nachiketas’s ultimate inquiry, Yama reveals the profound essence of all spiritual striving. He states that the supreme “goal which all the Vedas expound” – the ancient scriptures containing divine wisdom – and “which all austerities declare” – the various forms of rigorous spiritual discipline and self-control – is one and the same. Furthermore, it is “desiring which aspirants resort to Brahmacharya,” a state of disciplined celibacy and focused energy, undertaken for the sole purpose of spiritual advancement. This singular, ultimate objective, Yama concisely declares, is none other than the sacred syllable: “It is this – Om.” Om represents the totality of existence, the unmanifested and manifested Brahman, the cosmic vibration that underlies all creation, sound, and consciousness. It is the beginning, middle, and end of all spiritual paths, encapsulating the entire journey to ultimate reality in a single, potent sound.

1-II-16. Original Transliteration and Translation:

This syllable (Om) indeed is the (lower) Brahman; this syllable indeed is the higher Brahman; whosoever knows this syllable, indeed, attains whatsoever he desires.

Detailed Explanation:

Yama elaborates on the profound significance of the sacred syllable Om, revealing its dual nature as both the path and the ultimate reality. He explains that “This syllable (Om) indeed is the (lower) Brahman,” referring to Apara Brahman, the manifest, conditioned aspect of God, the creative principle that pervades the universe. Simultaneously, “this syllable indeed is the higher Brahman,” signifying Para Brahman, the transcendent, unmanifested, and absolute reality beyond all attributes. Therefore, Om encompasses both the personal and impersonal aspects of the Divine. Yama then declares the extraordinary power of realizing this truth: “whosoever knows this syllable, indeed, attains whatsoever he desires.” This is not an indulgence of worldly desires, but rather the fulfillment of all spiritual aspirations – liberation from the cycle of birth and death, ultimate peace, and union with the divine, as all true desires cease in the state of perfect knowledge.

1-II-17. Original Transliteration and Translation:

This support is the best; this support is the supreme. Knowing this support one is magnified in the world of Brahman.

Detailed Explanation:

Yama further emphasizes the unparalleled significance of Om as the ultimate spiritual anchor. He declares, “This support is the best; this support is the supreme,” highlighting Om as the most reliable and highest foundation for spiritual realization, transcending all other forms of worldly or temporary reliance. To truly grasp and internalize this profound truth – “Knowing this support” – is to embark on a transformative journey. The outcome is a remarkable expansion of consciousness: “one is magnified in the world of Brahman,” implying an absorption into the vast, infinite realm of ultimate reality. This signifies the dissolution of the limited individual ego and the realization of one’s true identity as boundless consciousness, interconnected with the very fabric of the cosmos.

1-II-18. Original Transliteration and Translation:

The intelligent Self is not born, nor does It die. It did not come from anywhere, nor did anything come from It. It is unborn, eternal, everlasting and ancient, and is not slain even when the body is slain.

Detailed Explanation:

Yama now delineates the eternal and immutable nature of the Self (Atman), distinguishing it from the perishable physical body. He declares that “The intelligent Self is not born, nor does It die,” emphasizing its timeless existence beyond the cycles of creation and dissolution. This divine essence is utterly primordial; “It did not come from anywhere,” possessing no origin point, “nor did anything come from It” in the sense of a prior cause, for it is the ultimate source. It is intrinsically “unborn, eternal, everlasting and ancient,” existing beyond the confines of linear time and the limitations of physical manifestation. Crucially, its essence remains untouched by physical demise: “and is not slain even when the body is slain.” This profound truth offers a timeless message of immortality, assuring that the true essence of an individual transcends the mortality of their physical form, providing solace and perspective on the transient nature of life.

1-II-19. Original Transliteration and Translation:

If the slayer thinks that he slays It and if the slain thinks of It as slain, both these do not know, for It does not slay nor is It slain.

Detailed Explanation:

This iconic verse beautifully underscores the profound, immutable nature of the Self, liberating it from the dualities of action and consequence that govern the material world. Yama reveals that true understanding transcends conventional perception: “If the slayer thinks that he slays It and if the slain thinks of It as slain, both these do not know.” The individual who believes they are capable of destroying the Self, and likewise, the one who imagines the Self can be destroyed, both operate from a state of fundamental ignorance. This is because the Self (Atman) is beyond all phenomenal change and interaction; “for It does not slay nor is It slain.” The Self is the eternal, witnessing consciousness, forever untouched by the comings and goings of forms, beyond the reach of violence, decay, or any act of termination. This wisdom liberates humanity from the fear of death and the illusion of absolute agency in the realm of finite existence.

1-II-20. Original Transliteration and Translation:

The Self that is subtler than the subtle and greater than the great is seated in the heart of every creature. One who is free from desire sees the glory of the Self through the tranquillity of the mind and senses and becomes absolved from grief.

Detailed Explanation:

Yama reveals the paradoxical and omnipresent nature of the Self, making it universally relatable. He explains that this divine essence is simultaneously “subtler than the subtle,” implying its imperceptible, formless nature beyond all material apprehension, and yet “greater than the great,” indicating its boundless, infinite pervasiveness, encompassing all existence. This profound Self “is seated in the heart of every creature,” signifying its immanent presence within the very core of all living beings, accessible to anyone who seeks inward. The path to realizing its magnificence is illuminated by inner discipline: “One who is free from desire” – having transcended the ceaseless craving for external gratification – “sees the glory of the Self through the tranquillity of the mind and senses.” Through such profound inner stillness and control, one gains direct perception of this radiant truth and, as a profound consequence, “becomes absolved from grief.” This liberation from sorrow is the ultimate freedom, found not by changing external circumstances, but by realizing the unchanging, blissful nature of the Self within.

1-II-21. Original Transliteration and Translation:

While sitting, It goes far, while lying It goes everywhere. Who other than me can know that Deity who is joyful and joyless.

Detailed Explanation:

This verse describes the paradoxical and transcendent nature of the Self (Atman), highlighting its freedom from the limitations of physical existence and conventional human understanding. “While sitting, It goes far,” implying that even in a state of apparent stillness, the Self is infinitely expansive and transcends all physical boundaries. “While lying, It goes everywhere,” further emphasizing its omnipresent and pervasive nature, unaffected by any posture or physical state. The rhetorical question, “Who other than me can know that Deity who is joyful and joyless,” speaks to the Self’s ultimate transcendence of all dualities. It is beyond the limited human concepts of pleasure and pain, happiness and sorrow. Only a fully realized being, like Yama (who embodies ultimate knowledge), can comprehend this ineffable aspect of the Divine, which exists in a state of absolute, unconditioned bliss, beyond all relative experiences.

1-II-22. Original Transliteration and Translation:

The intelligent one having known the Self to be bodiless in (all) bodies, to be firmly seated in things that are perishable, and to be great and all-pervading, does not grieve.

Detailed Explanation:

Yama reiterates the liberating insight of Self-realization, emphasizing its power to transcend suffering. The truly “intelligent one” is distinguished by their profound understanding of the Self: they know it “to be bodiless in (all) bodies,” recognizing that the eternal essence is distinct from and untouched by the physical form, even while residing within countless manifest beings. This Self is understood “to be firmly seated in things that are perishable,” meaning it is present as the unchanging substratum within all transient phenomena, yet remains unaffected by their decay. Furthermore, knowing it “to be great and all-pervading,” the wise perceive its infinite, expansive nature, encompassing all existence. This comprehensive realization leads to the ultimate freedom from sorrow: such an individual “does not grieve,” having transcended identification with the ephemeral and established their consciousness in the immutable, blissful Self.

1-II-23. Original Transliteration and Translation:

The Self cannot be attained by the study of the Vedas, not by intelligence nor by much hearing. Only by him who seeks to know the Self can It be attained. To him the Self reveals Its own nature.

Detailed Explanation:

This crucial verse dispels the misconception that spiritual liberation can be achieved through mere intellectual accumulation or external practices. Yama unequivocally states that “The Self cannot be attained by the study of the Vedas,” meaning intellectual mastery of scriptures alone is insufficient. Nor is it achieved “by intelligence” in the conventional sense of sharp reasoning or mental prowess, “nor by much hearing” of spiritual discourses without internal transformation. True Self-realization is a deeply personal and profound journey. “Only by him who seeks to know the Self can It be attained,” emphasizing that genuine, earnest longing and dedicated inner pursuit are the fundamental prerequisites. Ultimately, the Self reveals itself through its own grace: “To him the Self reveals Its own nature.” This highlights that Self-knowledge is not something acquired, but rather a profound unveiling, a direct experience granted when the seeker is truly ready and aligned with the truth.

1-II-24. Original Transliteration and Translation:

None who has not refrained from bad conduct, whose senses are not under restraint, whose mind is not collected or who does not preserve a tranquil mind, can attain this Self through knowledge.

Detailed Explanation:

This verse lays down the essential ethical and psychological prerequisites for attaining Self-realization, emphasizing that spiritual knowledge is not merely intellectual but requires a profound transformation of character and inner discipline. Yama states unequivocally that “None who has not refrained from bad conduct” – who continues to act in ways that harm themselves or others – can ever hope to realize the Self. Similarly, those “whose senses are not under restraint,” perpetually pulled by external desires, or “whose mind is not collected” and is perpetually agitated and fragmented, or “who does not preserve a tranquil mind,” cannot achieve this profound inner perception. Without this foundation of moral purity, sensory control, and mental stillness, the subtle truth of the Self remains elusive, for it requires a clear, quiet inner mirror to reflect its nature, a state that cannot be achieved amidst inner turmoil or unwholesome actions.

1-II-25. Original Transliteration and Translation:

The Self to which both the Brahmana and the Kshatriya are food, (as it were), and Death a soup, how can one know thus where It is.

Detailed Explanation:

This verse uses a powerful, almost shocking, metaphor to illustrate the absolute and all-encompassing nature of the Self, emphasizing its transcendence over all distinctions and powers within the manifest universe. Yama declares that the Self is so vast and ultimate that “both the Brahmana and the Kshatriya are food, (as it were).” These two classes represent the pinnacle of spiritual knowledge and worldly power, respectively, in ancient Indian society. Yet, in the presence of the Self, even their ultimate essences are absorbed and transcended. Furthermore, “Death a soup,” meaning even the formidable Lord of Death, the ultimate terminator, is ultimately consumed and integrated into the Self’s boundless reality. The rhetorical question, “how can one know thus where It is,” underscores the Self’s ineffability and incomprehensibility through ordinary means. It is not something that can be located or defined by conventional categories, as it is the very ground of all existence, beyond all distinctions, an ultimate reality that devours all dualities.

Chapter One – Part Three: The Chariot of the Self

1-III-1. Original Transliteration and Translation:

The knowers of Brahman and those who kindle the five fires and propitiate the Nachiketa Fire thrice, speak of as light and shade, the two that enjoy the results of righteous deeds, entering within the body, into the innermost cavity (of the heart), the supreme abode (of Brahman).

Detailed Explanation:

This verse introduces a profound mystical concept, often interpreted as the dual presence within the human heart. It is taught by “The knowers of Brahman” (those who understand the ultimate reality) and “those who kindle the five fires and propitiate the Nachiketa Fire thrice” (practitioners of advanced rituals). They speak of “light and shade” residing within the body – these are often understood as the Supreme Self (Paramatma) as the illuminating “light” and the individual soul (Jivatma) as the reflecting “shade.” Both are said to “enjoy the results of righteous deeds,” with the individual soul being the experiencer and the Supreme Self the witness. These two principles are described as “entering within the body, into the innermost cavity (of the heart),” which is recognized as “the supreme abode (of Brahman),” the sacred inner sanctuary where ultimate reality resides. This verse beautifully points to the coexistence of the individual and the universal within the depths of one’s own being.

1-III-2. Original Transliteration and Translation:

May we be able to know the Nachiketa Fire which is the bridge for the sacrificers, as also the imperishable Brahman, fearless, as well as the other shore for those who are desirous of crossing (the ocean of samsara).

Detailed Explanation:

This verse expresses a profound prayer for understanding both the means and the ultimate goal of spiritual endeavor. It is a wish to truly comprehend “the Nachiketa Fire which is the bridge for the sacrificers,” acknowledging its significance as a sacred path that leads to higher realms and temporary spiritual benefits. Crucially, the prayer also extends to understanding “the imperishable Brahman, fearless,” which represents the ultimate, unchanging, and absolute reality, beyond all fear and decay. This Brahman is further described as “the other shore for those who are desirous of crossing (the ocean of samsara),” symbolizing the ultimate liberation from the endless cycle of birth, death, and suffering. This prayer encapsulates the entire spiritual journey, from righteous action to supreme knowledge, aspiring to attain the profound state of fearlessness that comes with ultimate realization.

1-III-3. Original Transliteration and Translation:

Know the Self to be the master of the chariot, and the body to be the chariot. Know the intellect to be the charioteer, and the mind to be the reins.

Detailed Explanation:

Yama begins the famous and universally resonant “Chariot Metaphor,” a profound analogy for understanding the intricate relationship between the individual Self and its instruments of experience. He instructs Nachiketas, and by extension, all seekers, to “Know the Self to be the master of the chariot,” identifying the Atman or true essence of being as the ultimate passenger, the one for whom the journey is undertaken, yet distinct from the vehicle itself. The physical existence is likened to this vehicle: “and the body to be the chariot,” which is merely a temporary vessel for traversing the world. The crucial guiding force is then identified: “Know the intellect to be the charioteer,” representing the faculty of discernment (buddhi) and wise decision-making that guides one’s life path. Finally, the intricate control mechanism is revealed: “and the mind to be the reins,” signifying the mental faculty (manas) that channels impulses and directs the senses, acting as a link between the intellect and the instruments of experience. This metaphor beautifully illustrates the hierarchy of control necessary for a purposeful and guided life.

1-III-4. Original Transliteration and Translation:

The senses they speak of as the horses; the objects within their view, the way. When the Self is yoked with the mind and the senses, the wise call It the enjoyer.

Detailed Explanation:

Continuing the powerful Chariot Metaphor, Yama further defines the components that facilitate interaction with the external world. He explains that “The senses they speak of as the horses,” portraying them as powerful, energetic forces that propel the chariot forward and engage with the environment. The world around us, with all its myriad experiences, is then identified as “the objects within their view, the way,” representing the diverse pathways and landscapes encountered on life’s journey. Yama then reveals a crucial spiritual insight: “When the Self is yoked with the mind and the senses, the wise call It the enjoyer.” This means that when the true Self, the Atman, identifies or becomes entangled with the activities and perceptions of the mind and senses, it then perceives itself as the experiencer of pleasure and pain, attraction and aversion. This identification, while leading to the experience of the world, also creates the illusion of a limited “enjoyer,” binding the otherwise transcendent Self to the cycles of worldly experiences.

1-III-5. Original Transliteration and Translation:

But whoso is devoid of discrimination and is possessed of a mind ever uncollected – his senses are uncontrollable like the vicious horses of a driver.

Detailed Explanation:

Yama now contrasts the disciplined journey with a state of spiritual disarray, highlighting the consequences of lacking internal guidance. He explains that “But whoso is devoid of discrimination” (viveka) – lacking the essential spiritual insight to distinguish between the real and unreal, the eternal and the transient – “and is possessed of a mind ever uncollected” – one that is restless, agitated, and unfocused – such an individual’s “senses are uncontrollable.” Like wild, “vicious horses of a driver” that bolt without direction or heed, the senses, without the guiding hand of a discerning intellect and a collected mind, run rampant. This unrestrained pursuit of sensory gratification leads to a chaotic and unfulfilled existence, perpetually drifting from one fleeting desire to another, preventing any meaningful spiritual progress.

1-III-6. Original Transliteration and Translation:

But whoso is discriminative and possessed of a mind ever collected – his senses are controllable like the good horses of a driver.

Detailed Explanation:

In stark contrast to the previous verse, Yama now describes the ideal state of inner governance. He explains that “But whoso is discriminative” – possessing the profound wisdom to discern eternal truth from temporal illusion – “and possessed of a mind ever collected” – one that is focused, calm, and disciplined – such an individual achieves mastery over their internal instruments. For them, “his senses are controllable,” responding obediently to the direction of the intellect and the firmness of the mind. Like “the good horses of a driver,” these senses become instruments for purposeful action and spiritual progress, rather than sources of distraction and entanglement. This disciplined inner state is foundational for navigating the complexities of life with clarity and moving steadily towards liberation.

1-III-7. Original Transliteration and Translation:

But whoso is devoid of a discriminating intellect, possessed of an unrestrained mind and is ever impure, does not attain that goal, but goes to samsara.

Detailed Explanation:

Yama reiterates the dire consequences of spiritual indiscipline, emphasizing that the path to liberation is contingent upon profound inner transformation. He warns that “But whoso is devoid of a discriminating intellect” – lacking the capacity to discern truth from illusion – “possessed of an unrestrained mind” – one that is scattered, undisciplined, and swayed by every impulse – “and is ever impure” – referring to a state where actions, thoughts, and intentions are unwholesome and selfish – such an individual “does not attain that goal.” This means they fail to reach the ultimate spiritual realization, the state of liberation and union with the Divine. Instead, they remain trapped, continuing to experience the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth, endlessly returning “to samsara,” the realm of transient existence, suffering, and repetitive experience.

1-III-8. Original Transliteration and Translation:

But whoso is possessed of a discriminating intellect and a restrained mind, and is ever pure, attains that goal from which he is not born again.

Detailed Explanation: